[ad_1]

As COVID-19 relentlessly infects more and more of us, scientists are taking a close look at the bizarre and frightening damage it can inflict on our bodies.

We have known since the start of the pandemic that this disease wreaks havoc beyond the respiratory system, also causing gastrointestinal disturbances, heart damage and blood clotting disorders.

Now, a year after the start of the pandemic, extensive autopsies of patients with COVID-19 have revealed greater details of the inflammation and widespread damage in brain tissue. This may help explain the deluge of neurological symptoms that have manifested in some patients, from headaches, memory loss, dizziness, weakness and hallucinations to more severe seizures and strokes.

Some estimate that up to 50 percent of people hospitalized with COVID-19 could exhibit neurological symptoms that can cause people to have trouble doing even routine daily tasks like preparing a meal.

“We were completely surprised. We originally expected to see damage from a lack of oxygen, ”said Avindra Nath, physician and clinical director of the National Institute of Health (NIH).

“Instead, we saw multifocal areas of damage that are typically associated with stroke and neuroinflammatory disease.”

NIH researchers, including doctor Myoung-Hwa Lee and Nath, performed extensive brain tissue examinations of 19 deceased patients. They were between 5 and 73 years old and many had risk factors for severe coronavirus, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

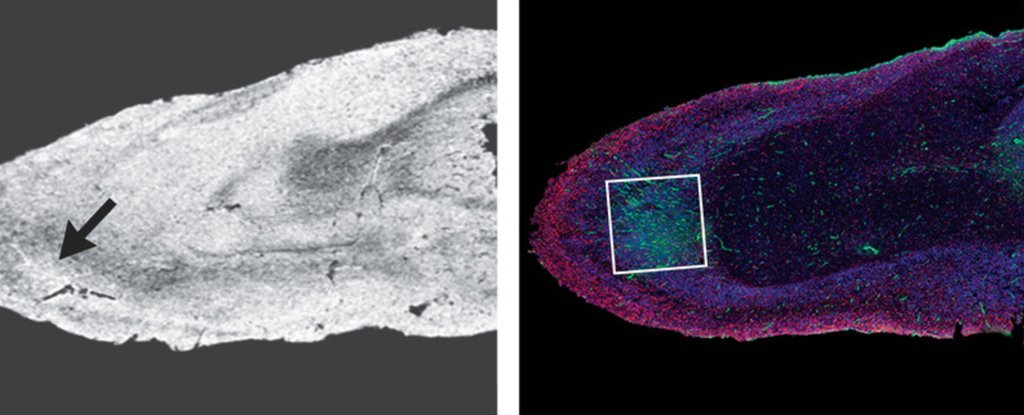

Using powerful MRI microscopy, Lee and his team identified 10 patients with brain abnormalities. Further examination under a microscope revealed hyperintensities – bright spots on the micrograph image of brain samples – which fluorescence microscopy revealed to be leaking fibrinogen (a blood protein).

T cells and the brain’s specialized immune cells, microglia, surrounded these spots in a number of patients; there were also dark areas of coagulated bleeding. These led the researchers to conclude that these patients had suffered multiple mini-brain bleeds – a type of damage typically associated with inflammation of the brain.

“The very small blood vessels in the brain were leaking,” Nath told NPR. “And it wasn’t evenly – you’ll find a little blood vessel here and a little blood vessel there.”

It was not only people seriously ill enough to require intensive care or have pre-existing conditions who exhibited neurological symptoms of COVID-19.

“We have seen this group of young people without conventional risk factors who have strokes, and patients with acute changes in mental status that are not otherwise explained,” said Benedict Michael, University neurologist. from Liverpool. Nature back in September.

The patients suffered from delusions and developed psychosis. In one case, a 55-year-old woman began seeing lions and monkeys in her home, before believing that a friend or family member had been replaced by an identical impostor (a Capgras illusion).

Despite tests to detect the virus in brain tissue, Lee and his team found no trace of SARS-CoV-2, but beware in their report: “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that the viral copy number was below the level of detection by our tests. “

While other studies have located traces of the virus in the brain, the levels were low and appear rare.

“So far, our results suggest that the damage we have seen may not have been caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus directly infecting the brain,” Nath said. Instead, the damage may be due to the body’s inflammatory response to the virus, he explained.

Due to the small sample size and limited clinical information, the team says they cannot draw any direct conclusions yet. But their results are consistent with EEG tests which revealed encephalopathy in COVID-19 patients – disruptions in the typical electrical activity of the brain that can signify swelling and inflammation.

It also aligns with studies showing that the virus can trigger other dangerous immune responses which, in some cases, do even more damage than the virus itself.

Researchers are concerned about the implications of brain inflammation for the long-term health of people, given that it is associated with memory loss and Alzheimer’s disease, and some patients are already suffering from lingering neurological consequences such as chronic fatigue and Guillain-Barré syndromes.

“In the future, we plan to study how COVID-19 harms blood vessels in the brain and whether it produces some of the short and long term symptoms that we see in patients,” Nath said.

Their report was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

[ad_2]

Source link