[ad_1]

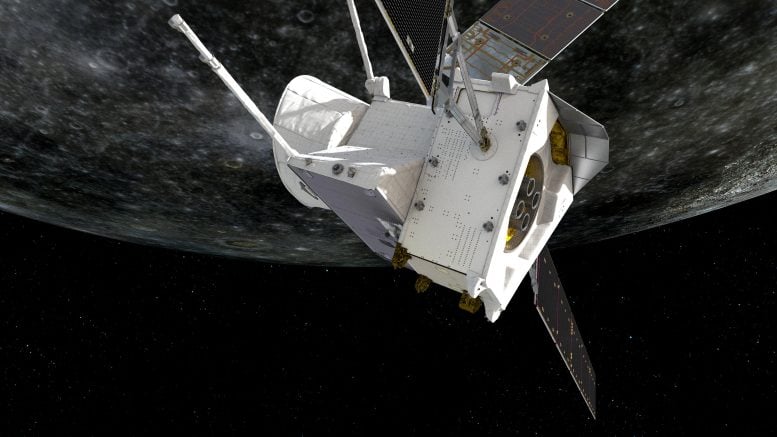

Artist’s impression of BepiColombo flying by Mercury on October 1, 2021. The spacecraft performs nine gravitational assistance maneuvers (one from Earth, two from Venus and six from Mercury) before entering orbit around the most internal solar system in 2025. Credit: ESA / ATG media laboratory

ESA /JAXA The BepiColombo mission captured its first views of its destination planet Mercury as it nosed down during a close-range gravity-assisted flyover last night.

The closest approach was at 11:34 p.m. UTC on October 1, 2021, at an altitude of 199 km above the surface of the planet. Images from the spacecraft’s surveillance cameras, as well as scientific data from a number of instruments, were collected during the meeting. The images have already been uploaded on Saturday morning and a selection of first impressions are shown here.

-

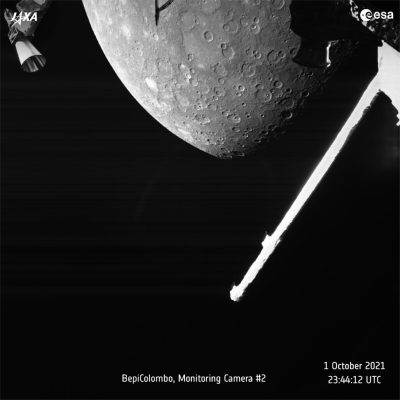

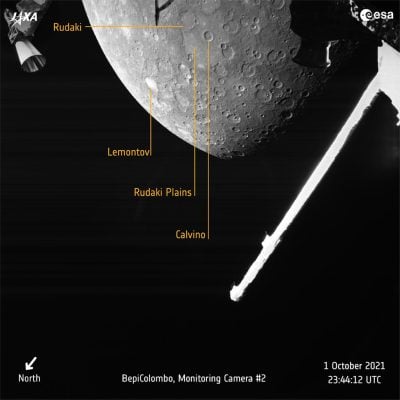

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:44:12 UTC by Mercury Transfer Module Surveillance Camera 2, while the spacecraft was approximately 2,418 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

-

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:44:12 UTC by Surveillance Camera 2 of the Mercury Transfer Module, while the spacecraft was approximately 2,418 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

“The flyby was flawless from a spacecraft perspective, and it’s amazing to finally see our target planet,” said Elsa Montagnon, spacecraft operations manager for the mission.

The surveillance cameras provide black and white snapshots with a resolution of 1024 x 1024 pixels and are positioned on the Mercury transfer module to also capture the structural elements of the spacecraft, including its antennas and the boom of the magnetometer.

The images were acquired approximately five minutes after the time of the close approach and up to four hours later. Because BepiColombo arrived on the night side of the planet, conditions were not ideal for taking images directly at the closest approach, so the closest image was captured at a distance of approximately 1000 km .

In many images, it is possible to identify large impact craters.

-

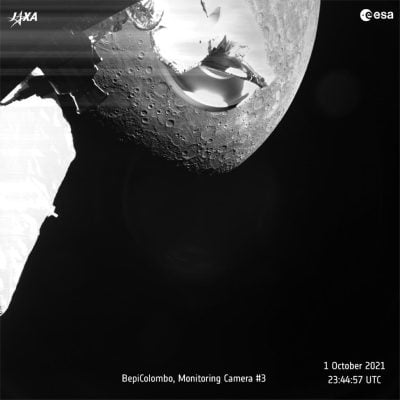

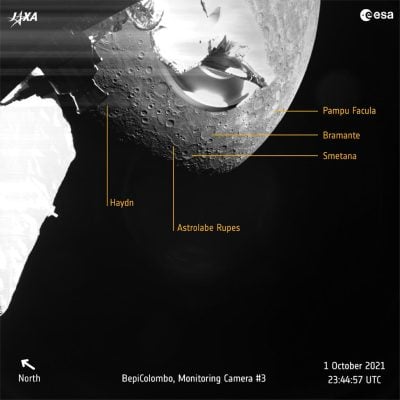

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. This image was taken at 23:44:57 UTC by Surveillance Camera 3 of the Mercury Transfer Module, while the spacecraft was 2,687 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

-

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. This image was taken at 23:44:57 UTC by Surveillance Camera 3 of the Mercury Transfer Module, while the spacecraft was 2,687 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

“It was an incredible feeling to see these almost live images of Mercury,” says Valetina Galluzzi, co-investigator of BepiColombo’s SIMBIO-SYS imaging system that will be used once in orbit of Mercury. “It really pleased me to meet the planet that I have studied since the very early years of my research career, and I look forward to working on new images of Mercury in the future.”

“It was very exciting to see the first images of Mercury from BepiColombo and understand what we were seeing,” said David Rothery of the UK Open University, who heads the surface and composition working group. of mercury from ESA. “It made me even more excited to study the high quality scientific data that we should get when we orbit Mercury, because it is a planet that we do not yet fully understand.”

-

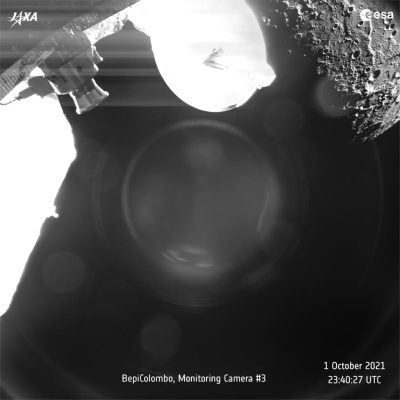

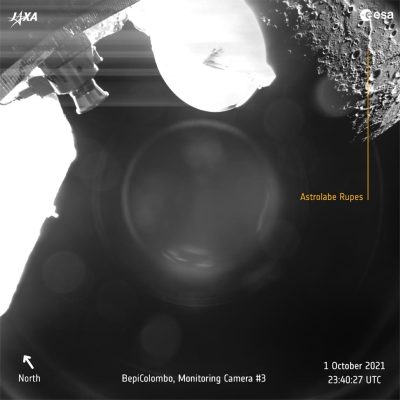

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:40:27 UTC by surveillance camera 3 of the Mercury transfer module, while the spacecraft was 1183 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

-

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:40:27 UTC by surveillance camera 3 of the Mercury transfer module, while the spacecraft was 1183 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Although the crater’s surface looks like Earth’s Moon at first glance, Mercury has a much different story. Once its main scientific mission begins, BepiColombo’s two scientific orbiters – ESA’s Mercury Planetary Orbiter and JAXA’s Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter – will study all aspects of the mysterious Mercury from its nucleus to surface processes, the magnetic field. and the exosphere, in order to better understand the origin and evolution of a planet close to its mother star. For example, he will map the surface of Mercury and analyze its composition to learn more about its formation. One theory is that it may have started out as a larger body which was later stripped of most of its rock by a giant impact. This left it with a relatively large iron core, where its magnetic field is generated, and only a thin outer rocky shell.

Mercury has no equivalent to the ancient brilliant lunar highlands: its surface is dark almost everywhere and was formed by vast lava effusions billions of years ago. These lava flows bear the scars of craters formed by asteroids and comets crashing onto the surface at speeds of tens of kilometers per hour. The soils of some of the oldest and largest craters have been inundated by more recent lava flows, and there are also over a hundred sites where volcanic explosions have ruptured the surface from below.

-

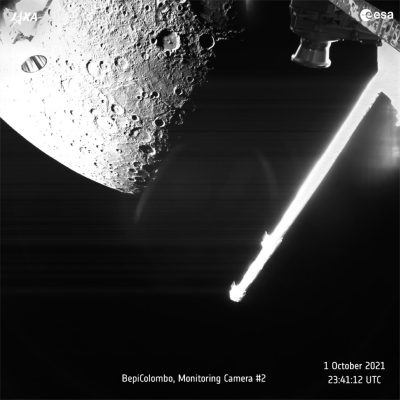

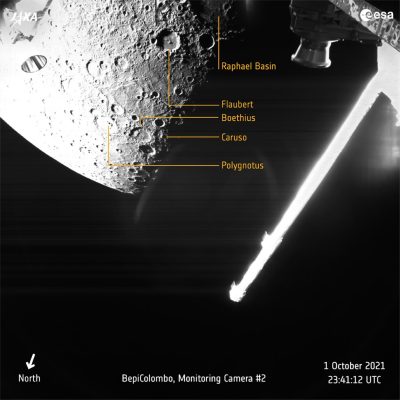

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:41:12 UTC by Mercury Transfer Module surveillance camera 2 while the spacecraft was 1410 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

-

BepiColombo captured this view of Mercury on October 1, 2021, as the spacecraft flew over the planet for a gravitational assist maneuver. The image was taken at 23:41:12 UTC by Mercury Transfer Module surveillance camera 2 while the spacecraft was 1410 km from Mercury. Credit: ESA / BepiColombo / MTM, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

BepiColombo will explore these themes to help us better understand this mysterious planet, drawing on data collected by Nasathe Messenger mission of. It will address questions such as: What are the volatile substances that transform violently into gas to fuel volcanic explosions? How did Mercury retain these birds if most of its rock was removed? How long has the volcanic activity persisted? How fast does Mercury’s magnetic field change?

“In addition to the images we got from the surveillance cameras, we also used several scientific instruments on the Mercury Planetary Orbiter and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter,” adds Johannes Benkhoff, scientist from ESA’s BepiColombo project. “I can’t wait to see these results. It was a fantastic night shift with fabulous teamwork and many happy faces.

BepiColombo’s main scientific mission will begin in early 2026. It uses a total of nine planetary flyovers: one on Earth, two on Earth. Venus, and six to Mercury, as well as the spacecraft’s solar electric propulsion system, to help navigate Mercury’s orbit. Its next flyby of Mercury will take place on June 23, 2022.

[ad_2]

Source link