[ad_1]

"The guidelines do not advocate a mandatory or abrupt dose reduction or discontinuation, as these actions can be harmful to the patient," said Redfield in his letter, published the day after the FDA warning. "The guideline includes recommendations for clinicians to work with patients to reduce or reduce dosage only when the harm suffered by the patient outweighs the patient's benefits from opioid therapy. "

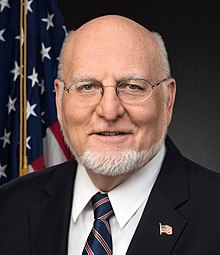

Redfield has been director of the CDC for a little over a year. This letter is his most comprehensive public comment to date on the opioid guideline, which was intended only for primary care physicians treating chronic non-cancer pain. Redfield pointed out that physicians and patients should collaborate on phased-down plans, but only "if a patient wants to gradually reduce".

"The guideline also recommends that the plan be based on the patient's goals and concerns and that the progressive reduction be slow enough to minimize opioid withdrawal," said Redfield.

"We are very grateful to the CDC for its critical insights," said Sally Satel, MD, of the American Enterprise Institute and Yale University, who helped write the letter HP3. "The time has come for federal, state, and non-government institutions that have invoked the authority of the CDC to apply some traumatic changes to care to turn the tide."

"Close the door of the barn"

Critics, however, wonder why it took the CDC three years to recognize that the guideline had been largely implemented beyond its original purpose.

"I find it striking that, while the CDC has made statements from time to time about its intention not to transform the directive into laws and regulations, this statement is the most daring statement it has made to date. have legislated on part of the guideline, not to mention the steps taken by the payers, "said Bob Twillman, PhD, former executive director of the Association of Integrative Pain Management.

"If they really did not expect that to happen, they were incredibly naive, because many of us made public statements predicting these results when the line was published. director. I know that some patient advocates hope this will lead to the resolution of some legislation, but I think it's a very long-term project. In other words, it's a bit like closing the barn door after the horse has already escaped.

When it released its opioid guideline in 2016, the CDC is committed to assessing the expected and unintended consequences and announced that it will make changes to the recommendations if necessary. Redfield's letter contains a three-page attachment summarizing the agency's efforts to assess the impact of the guideline. A close reading of the attachment, however, shows that most of the ongoing studies are not conducted by the CDC itself and focus primarily on whether the recommendation has been successful in reducing opioid prescriptions. and not if it hurts patients.

"Honestly, I do not think it's such a bad thing that CDC supports external work to evaluate the impact of the guideline. Having independent researchers who may not be as likely to feel the need to defend the guideline can only be helpful, "said Twillman.

"I feel that it's a political delay to avoid having to admit that the CDCs were fundamentally wrong," said Richard "Red" Lawhern, PhD, director of the Alliance research for the treatment of insoluble pain (ATIP). "The letter from the CDC director has doubled several" initiatives "that seem to assume that the original assumptions and statements of the guidelines were correct – which was not the case and for which there is a lot of published evidence that is not . . "

Lawhern wrote an open letter to Redfield this week calling for the revocation of the CDC's directive, not just its clarification, as many of its key assumptions about the potential for addiction to prescription opioids are untrue.

In a recent PNN survey of nearly 6,000 patients, more than 85% said the guidelines had worsened their pain and quality of life. Nearly half say they have considered suicide because their pain is poorly treated. Many patients hoard opioids because they fear that they will not have access to them and that some people turn to other substances, legal or illegal, to relieve pain.

[ad_2]

Source link