[ad_1]

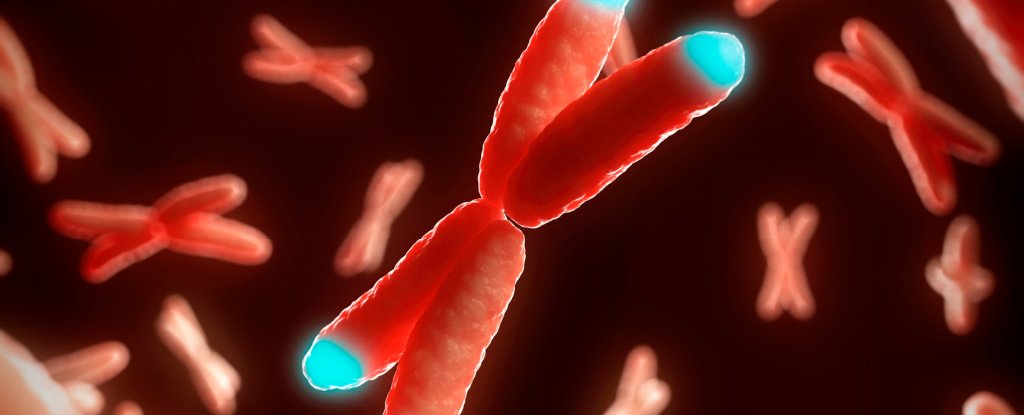

Every time a cell inside your body replicates, a slip of your youth crumbles to dust. This happens through the shortening of telomeres, the structures that “cap” the ends of our chromosomes.

Now, Israeli scientists say they were able to reverse this process and extend telomere length in a small study involving 26 patients.

Participants sat in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber for five 90-minute sessions per week for three months, and as a result, some telomeres in their cell were prolonged by up to 20%.

It’s an impressive claim – and something that many other researchers have attempted in the past without success. But of course, it’s worth pointing out that this is a small sample size and the results will need to be replicated before we get too excited.

However, the fact that hyperbaric oxygen therapy appears to affect telomere length is an inescapable link that merits further investigation.

Lead researcher Shair Efrati, a doctor at Tel Aviv University’s Faculty of Medicine and Sagol School of Neuroscience, told ScienceAlert how the inspiration behind their experiment was somewhat out of this world.

“After the twin experiment performed by NASA, where one of the twins was sent into space and the other remained on Earth, demonstrated a significant difference in the length of their telomeres, we realized that changes in the external environment can affect the cell nucleus – changes that occur with aging, ”Efrati said.

Telomeres are repeating pieces of code that act like the DNA equivalent of the plastic or metal aglet on the end of a lace.

They copy themselves with the rest of the chromosomes every time a cell divides. Yet with each replication, tiny snippets of code from the tip of the sequence fail to make the new copy, leaving the newly minted chromosome a bit shorter than its predecessor.

As anyone who has lost their lace cap knows, it doesn’t take long for the lace to lose its integrity. Likewise, shorter telomeres place sequences lower in the chromosome at a higher risk of dangerous mutations.

These mutations coincide with changes that predispose us to a bunch of age-related conditions, including all diseases such as cancer.

That doesn’t necessarily mean we’re getting older because our telomeres are shrinking, but there is a link between telomere length and health that researchers want to explore.

“Longer telomeres correlate with better cell performance,” Efriti explained.

There are many ways to accelerate the erosion of our telomeres. Not getting enough sleep could do this, as could eating too many processed foods and maybe even having children.

Slowing the loss takes a little more effort, but exercising regularly and eating well are good bets if you want your chromosomes to stay on for as long as possible.

A real success would be to turn our chromosomal hourglass completely and restore lost telomere sections. The fact that the high-turnover tissues in our gut do this naturally using an enzyme called telomerase has fueled research over the years.

There have been many milestones in the attempts to accomplish this task. Gene therapy in mice has shown that it may one day be feasible in humans. More recently, the stem cells of a super-centennial woman had their telomeres completely reset outside of her body.

Some studies have found a potential for an increase of as little as perhaps a few percent with the provision of nutritional supplements such as vitamin D.

But while there are a lot of high-profile promises to reverse aging in living humans already on the market, the reality of the science-based therapies we can use to give ourselves a 20-year-old’s telomeres has was disappointing.

This is why the latest study is attracting so much attention. Far from a measly two or three percent, this latest study found that telomeres in white blood cells taken from 26 subjects had regained about a fifth of their lost length.

The key, it seems, is hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) – the absorption of pure oxygen while sitting in a pressurized chamber for long periods of time; in this case, five 90-minute sessions per week for three months.

HBOT has generated controversy in the past for claims that it could treat a range of conditions. This is usually the kind of therapy you give to a diver who has come too quickly from the depths of the ocean, or to kill oxygen-sensitive germs in a wound that won’t heal otherwise.

But oxygen-rich environments also create a strange paradox, one where the body desperately elicits a host of genetic and molecular changes that typically occur in a low-oxygen environment.

In this study, the researchers were able to show that the genetic changes caused by HBOT extended the telomeres and also had a potentially positive effect on the health of the tissues themselves.

A slightly smaller sample of volunteers also showed a significant decrease in the number of senescent T cells, tissues that are a vital part of our immune system’s targeted response against invaders.

Whether you sit in a small tank every day for a quarter of a year is a matter of preference, but future research may help make the whole process more efficient, at least for some.

“Once we have demonstrated the effect of reverse aging on the study cohort using a predefined HBOT protocol, further studies are needed in order to optimize the specific protocol per individual,” Efrati told ScienceAlert.

In a press release from the Sagol Center for Medicine and Hyperbaric Research, Efrati says that understanding telomere shortening is “considered the ‘holy grail’ of the biology of aging.”

As important as telomere shrinkage seems to be, the failure of our biology as we age is undoubtedly a complicated issue involving more than just chunks of lost chromosomes.

Telomerase reactivation is also a trick that cancers use to stay ahead of the growth curve, making this holy grail a potentially poisoned chalice that we need to understand better before we drink too much.

Interestingly, research like this will help us develop a better picture of the aging process.

This research was published in Aging.

[ad_2]

Source link