[ad_1]

A meteorite from Costa Rica may contain answers to the biggest questions about how life began on planet Earth. Scientists from School of Geology of Central America are studying parts of a 2019 meteorite that impacted Aguas Zarcas, a village in the tropical rainforest of Costa Rica, described as “more precious than gold”. The Costa Rican meteorite could provide a cosmic library of new information on how life began on earth billions of years ago.

According to a 2017 paper by scientists from McMaster University and the Max Planck Institute , life on earth began 3.7 to 4.5 billion years ago after a series of meteorites filled with essential chemicals crashed into ponds of hot liquid. A series of wet and dry cycles then brought together the basic molecular building blocks of life in these nutrient-rich ponds. And then miraculously, our planet’s first self-replicating RNA molecules emerged, providing the first lines of genetic code that would eventually evolve into all life on earth.

An unusual arrowhead-shaped meteorite from the fall of Aguas Zarcas. This sample belongs to the private collector, Michael Farmer. (Laurence Garvie / Center for Meteorite Studies, Arizona State University )

Hot cosmic rocks can confirm or refute the Big Bang theory

A Science Mag The article says that on April 23, 2019, just after 9 p.m., a “fiery emissary,” the so-called Aguas Zarcas meteor, crossed the Costa Rican sky in a streak of supernatural orange and green light. This interstellar visitor has been described as the size of a washing machine. It fragmented as it passed through Earth’s protective atmosphere and crashed into the jungle. This meteorite from Costa Rica is made up of the same chemical elements that struck the earth’s crust just before life began billions of years ago.

Scientists collected a total of 60 pounds (27 kilograms) of meteorite fragments at Aguas Zarcas, the largest piece weighing about 4 pounds (1.8 kilograms). According to the researchers, the carbon in this meteorite was “formed from the nuclear fission of stars and its origin.” And trapped in this “rock” were molecular fragments of water, nickel and sulfur, the same isotopes that make up the sun. Currently, these hot cosmic rocks are being analyzed. This research may lead to a better understanding of exactly how life formed on earth and confirm or disprove the Big Bang theory.

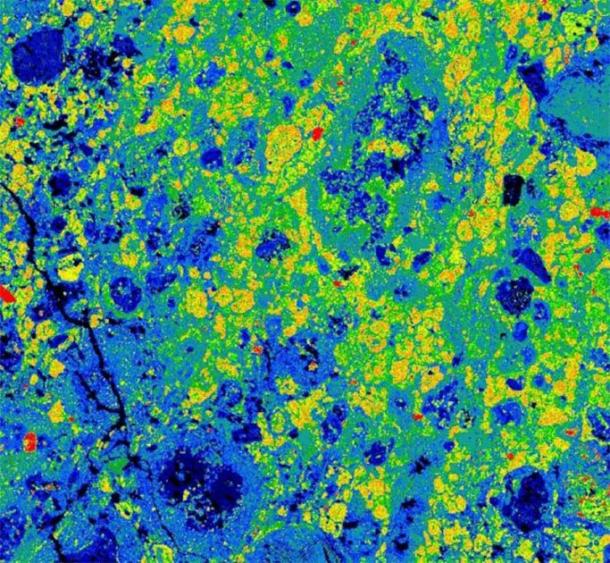

This colorful image is a composite element map showing the distribution of different minerals on a microscopic scale in a fragment of the Aguas Zarcas meteorite. Orange-yellow colors show the distribution of a mineral called tochilinite, dark blue colors represent olivine, and red colors are pentlandite and pyrrhotite. (Laurence Garvie / Center for Meteorite Studies, Arizona State University )

How the Costa Rican meteorite fragments were found

Each year, tens of thousands of meteorites pass through the Earth’s atmosphere and 99% of them fragment into molecular dust. However, some coins are coming to earth. To date, more than 60,000 have been found and classified by scientists. But meteor strikes that have been observed are exceptionally rare. Science Mag said that “only 1,196 have been registered”. The Aguas Zarcas 2019 impact event was seen by many, and a woman found a piece right after it landed.

Marcia Campos Muñoz resisted the sale of her biggest piece of meteorite, even as its value exceeded that of gold. (Andrea Solano Benavides / AAAS)

According to Science Mag, Marcia Campos Muñoz was in her pajamas on the sofa just after 9 p.m. when she heard “an ominous growl”. Her heart was pounding and her animals panicked as the meteor “made the house shake to its bones.” As the smoke cleared, she found “a grapefruit-sized hole in the corrugated zinc roof and a shattered plastic table” and under that mess, the charred black meteorite strewn across the ground. Not afraid of radiation poisoning, unlike typical movie scenarios, Marcia picked up the larger fragment. She said it was still warm to the touch. Within hours, a local reporter visited the house and posted videos of the cosmic damage and evidence to a live Facebook video.

Cosmic gems more valuable than gold

The legal and illegal market for meteorite fragments is fueled by geological treasure hunters who scour fields and deserts in search of rare rocks that they often share and sell to scientific geologists.

The Fukang meteorite, made of nickel and iron intertwined with olivine (green) crystals, believed to be around 4.5 billion years old, provides a good example of the value of space rocks. Discovered in 2000, generally named after the region where it landed, the Fukang meteorite is considered the most beautiful meteorite ever discovered. And, believe it or not, a piece of Fukang meteorite weighing 68 pounds (31 kilograms) sold for an astonishing $ 2 million (1.7 million euros)!

AJ Timothy Jull, editor-in-chief of the journal Meteorites and planetary science , tells such incredible valuations that opportunistic space rock hunters in Costa Rica may soon be regulated, as governments around the world realize the potential value of finding and selling rocks that may hold the secrets of life on earth .

Top image: This tiny and bright Costa Rican meteorite fragment from Aguas Zarcas may contain amino acids, as well as pre-sun stardust. Source: Laurence Garvie / Center for Meteorite Studies, Arizona State University

By Ashley Cowie

[ad_2]

Source link