[ad_1]

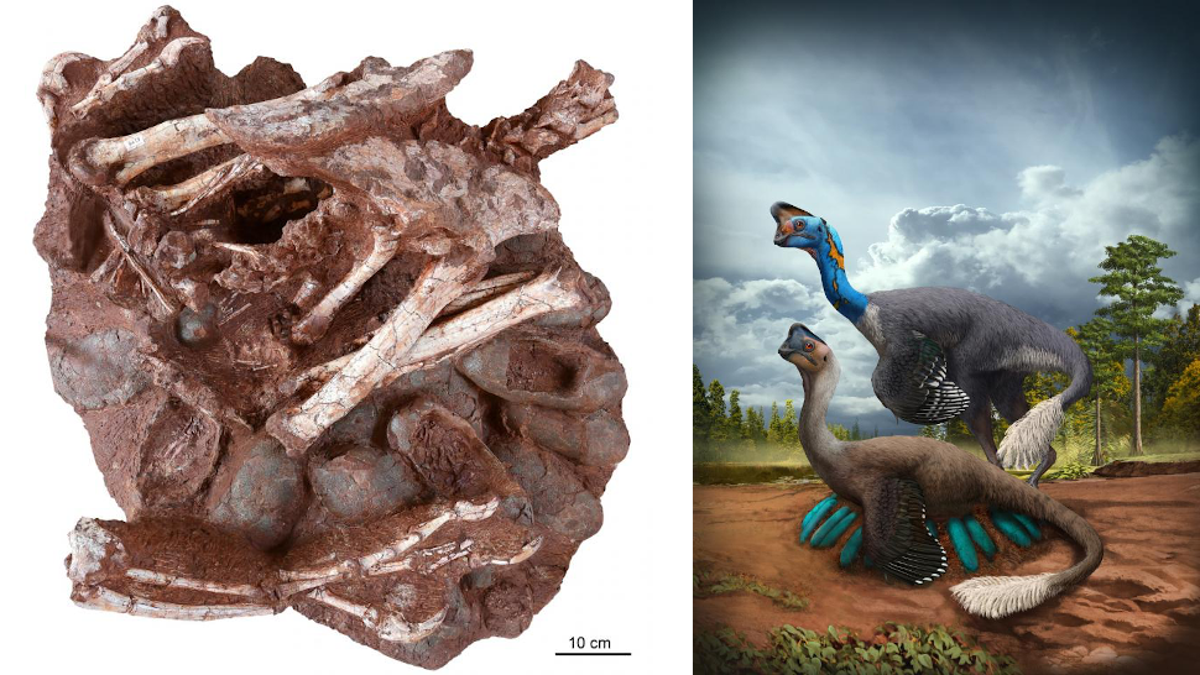

Paleontologists in China have unearthed the fossil of an oviraptorosaur sitting on an egg nest. In itself, this is an amazing and rare find, but this fossil is unique in that the eggs still retain evidence of unhatched progeny. inside.

“Here we report the first [non-avian] dinosaur fossil known to preserve an adult skeleton on top of a clutch of eggs that contains embryonic remains, ”say the authors of a search paper published in Science Bulletin. Found in China, the fossil expands our understanding of the behavior and physiology of oviraptorosaurs, while providing further evidence that non-avian dinosaurs used bird-like brooding behaviors.

Oviraptorosaurs, also known as oviraptors, were named as such due to an early paleontological misunderstanding of similar fossils. The name means “egg thief,” but these dinosaurs were not thieves, as oviraptorosaurs were later shown to be the rightful owners of the fossilized eggs often found alongside their buried skeletal remains.

Indeed, fossils of nesting oviraptorosaurs with their eggs have already been found. What’s new here is that dinosaur eggs still have evidence of embryos inside. It should be noted that embryos in oviraptor eggs have already been found, but only in isolation. A famous example is the “Baby Louie”Fossil, discovered in Henan, China, in the 1990s.

G / O Media can get a commission

Oviraptorosaurs were a very successful theropod dinosaur from the Cretaceous Period. They varied greatly in size, with some of the larger ones weighing over 2,425 pounds (1,100 kilograms). Common features include feathers, a long neck, wings, and beaks. These non-avian dinos looked a lot like birds, resembling modern ostriches. When nesting, these animals arranged their eggs in an almost perfect circle, layering their large clutches of eggs in a remarkably orderly fashion.

The newly described fossil, designated LDNHMF2008, was mined from the Nanxiong Formation near the Ganzhou Railway in southern China’s Jiangxi Province. The fossil dates from the late Cretaceous period, around 70 million years ago. It preserves the remains of a medium-sized adult oviraptorosaur, with its skull and other skeletal features missing. The animal appears to have died in the nesting position.

These fossilized bones were found alongside an “undisturbed clutch” of at least 24 eggs, “some of which are broken, exposing embryonic bones,” the study authors wrote. The researchers, led by Shundong Bi of Indiana University of Pennsylvania and Xing Xu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, attributed the eggs to fossil species. Macroolithus yaotunensis.

Oviraptorosaur nests containing so many eggs at the same time are not uncommon, and probably an adaptation to extreme poaching by true “egg thieves”.

Microscopic analysis of the fossils showed that some embryos were in the late stages of development and were about to hatch. The authors saw this as potential evidence that oviraptors were actively incubating their nests, and not just guarding them, as some paleontologists have speculated.

“In the new specimen, the babies were almost ready to hatch, which tells us without a doubt that this oviraptorid had maintained its nest for quite a long time,” Matthew Lamanna, paleontologist at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and co-author of the short story study, said in a report. “This dinosaur was a caring parent who ultimately gave his life while feeding his young.”

Other evidence confirmed this interpretation, namely an analysis of oxygen isotopes showing that the eggs were incubated at high temperatures, similar to those of birds, around 97 to 100 degrees Fahrenheit (36 to 38 degrees Celsius). . Interestingly, the eggs were shown to be at different stages of development, meaning they hatched at different times. That’s what we call asynchronous hatching, a reproductive phenomenon observed in modern birds. The authors were unable to attribute a cause to the asynchronous outbreak, but they presented a plausible scenario, as they write in their study:

“As in ostriches, oviraptorosaurs would not have started incubating the nest until after all the eggs had laid, so that the lower eggs, which had been laid earlier, would have been incubated proportionally the same time as the eggs. superiors. However, the upper eggs would have hatched earlier than the lower ones because, being closer to the brooding adult, they would have received more heat from that individual than the lower eggs, and therefore the embryos would have developed faster.

Finally, the scientists also detected a handful of pebbles in the dino’s abdominal region. These rocks are probably gastroliths, which animals swallow to aid digestion. This is the first time such a thing has been documented in an oviraptorosaur, and a potential clue to their diet. That’s admittedly a ton of new perspectives for a single fossil, albeit remarkable.

“It’s extraordinary to think of the amount of biological information captured in this single fossil,” said Xu. “We will learn from this specimen for many years to come.”

[ad_2]

Source link