[ad_1]

NOTASA deputy administrator Jim Morhard has perhaps one of the most low-key public reactions to the presidential election result.

“It’s a day for everyone, to say the least,” he said at the start of a presentation on November 7 at the SpaceGen Summit of the Space Generation Advisory Council, just three hours after a series of media screenings, from The Associated Press to Fox News, declared Joe Biden the winner. He did not expand on this comment and immersed himself in his previously scheduled speech on the agency’s activities.

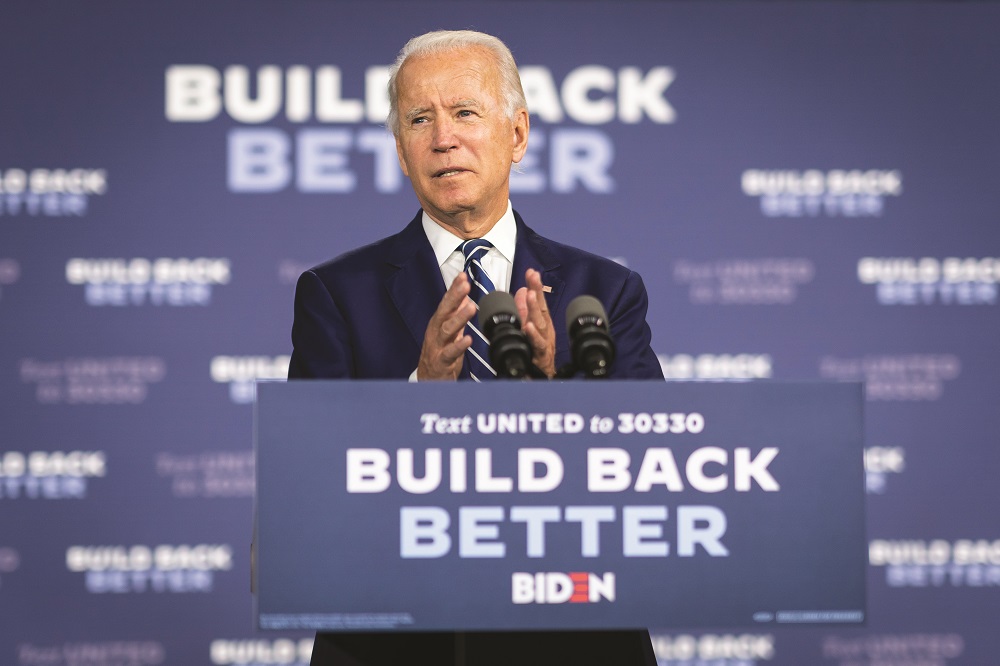

Whether the result sparked elation or disappointment, Joe Biden’s election has left the space industry wondering what will come next. While Biden is a familiar figure in politics, after decades in the Senate and eight years as Barack Obama’s vice president, his views on space and his plans for NASA are much less clear.

BIDEN SPACE POLICY

The Biden campaign said almost nothing about space during the White House race, other than a few statements praising NASA on the successful launch and return of the Demo-2 commercial crew mission this summer. “As President, I look forward to leading a bold space program that will continue to send hero astronauts to expand our frontiers of exploration and science through investments in research and technology to help millions of people here on Earth, ”he said in one of those statements. .

“One of the things that I found surprising was that the Biden campaign did not release a space policy statement,” said John Logsdon, founder and former director of the Space Policy Institute at George University. Washington. “So we are left with the platform the Democratic Party said.”

This platform included a paragraph on space that Logsdon considered “very positive”, if not without much detail. The platform endorsed, in broad terms, much of what NASA was doing now, from scientific and technological development to the continued operation of the International Space Station and human space exploration.

Most of the space industry players who read this passage made two major changes that a Biden administration would pursue. The platform mentions the “strengthening” of Earth observation programs at both NASA and NOAA “to better understand the impact of climate change on our home planet”. This is part of a broader focus on climate change, which is one of the four priorities identified by the new Biden administration alongside COVID-19, economic recovery and racial equity.

“Managing the Earth’s ability to sustain human life and biodiversity will likely dominate, in my opinion, a civilian space agenda for a Biden-Harris administration,” predicted Lori Garver, former NASA deputy administrator under the Obama administration, during a November 7 speech at the SpaceVision 2020 conference by students for the exploration and development of space.

It is not clear exactly how this will be implemented. One possibility would be to speed up the implementation of the Decennial Earth Science Survey with additional funding. “NASA is a national asset, and if properly directed and nurtured, we can make significant contributions to sustaining humanity,” Garver said.

The other change concerns human space exploration. While the platform said the party supported “NASA’s work to bring Americans back to the moon and beyond Mars,” it made no mention of a date to do so, in especially the 2024 date set by the Trump administration last year. This has led to speculation that the Biden administration will at least slow down the Artemis program, possibly freeing up money for earth sciences and other priorities elsewhere in the agency.

“I don’t think Artemis will be canceled. I also don’t think he will get more money than he is currently receiving, ”said Wendy Whitman Cobb, a professor at the US Air Force School of Advanced Air and Space Studies whose research includes space policy.

A human lunar landing in 2024 could be ruled out even before Biden is sworn in on January 20. surface of the moon. The House, however, provided only about $ 600 million for HLS in a spending bill passed in July.

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine, while publicly thanking the House for providing at least some money for HLS, lobbied the Senate for full funding to keep a 2024 landing in the deadlines. “Accelerating it through 2024 requires a budget of $ 3.2 billion for 2021 for the human landing system, which is part of the president’s budget request,” he told Senate officials in September.

The latter released their spending bills on November 10, which will serve as the basis for negotiations with the House on a final version. For NASA, they provided $ 1 billion for the HLS program, more than the House but still far from the budget request. In the report accompanying the bill, Senate officials noted that the uncertainty surrounding the program “makes it difficult to analyze the future impacts that funding for the accelerated Moon mission will have on other important NASA missions. .

HLS funding was just one obstacle to a human landing in 2024 identified in a report from the NASA Inspector General’s office on Nov. 12 that discussed the agency’s main challenges, also citing delays in the space launch system and Orion. He concluded that NASA “will find it difficult to land astronauts on the moon by the end of 2024”.

“I don’t know of anyone who thinks we’re going to get there by 2024,” Garver said. “It didn’t matter who won, it was going to be an impossible goal.”

TRANSITION TEAM

While the incoming administration’s plans for NASA are not certain, they are working on this transition quickly. On November 10, he announced the lists of agency review teams, or transition teams, which will be spread across the federal government to gather information to guide planning for the new administration.

“The transition teams really come to see how things are going and make recommendations for the future,” said Garver, who led NASA’s transition team for the new Obama administration in 2008.

The agency review team for NASA is full of people who previously worked in the agency or who know it very well. Leading the team is Ellen Stofan, a planetary scientist who served as NASA’s chief scientist under the Obama administration and is now director of the National Air and Space Museum. Waleed Abdalati, his predecessor as NASA’s chief scientist, is also on the team. He co-chaired the most recent ten-year earth science survey.

Others have extensive NASA experience. Pam Melroy is a former NASA astronaut who flew on three shuttle missions and went on to work in the FAA’s Commercial Space Office and DARPA. Dave Noble, Shannon Valley, and David Weaver all held NASA policy and communications positions during the Obama administration; Valley is also a climatologist.

Bhavya Lal, a researcher at the Institute for Science and Technology Policy, has studied a wide range of space-related topics for NASA and other government agencies. Jedidah Isler, assistant professor at Dartmouth, has not previously worked for NASA, but her research in astrophysics complements the scientific backgrounds of other members of the team.

However, when the team can start working, it is not clear. The Trump administration has been slow to recognize Biden’s victory, and the head of the General Service Administration, which controls resources for presidential transitions, has yet to release those resources for the Biden transition. NASA officials did not respond to questions from Nov. 12 about whether it had entered into discussions with the agency’s review team or on advice it received from the White House to support the transition.

DIRECTOR CANDIDATES

Another priority for the Biden transition is choosing a new NASA administrator. Although it was confirmed in a close Senate vote in April 2018, Bridenstine had convinced members of Congress on both sides of the aisle for his leadership of the agency. Some in the space community hoped that even with Biden’s victory, Bridenstine could stand.

Bridenstine, however, plans to leave the agency at the end of the Trump administration, telling Aerospace Daily that he “wouldn’t be the right person” to run the agency in a Biden administration. President-elect Biden’s NASA transition team The NASA administrator, he said, needed to have a “close relationship” with the White House, which he lacked, a former member of the Republican Congress.

While Biden’s transition has been low-key over his choice of a new director, there has been a lot of speculation, dating back long before the election, about potential candidates for the job. This list is dominated by women, like Melroy, the former astronaut on the Transition Team. Others include Wanda Austin, former president and CEO of The Aerospace Corporation; Gretchen McClain, a former NASA public servant who went on to work in industry and sits on the board of directors of several companies, such as Booz Allen Hamilton; and Wanda Sigur, former vice president and general manager of civil space at Lockheed Martin.

Another possibility is Rep. Kendra Horn (D-Okla.), Who lost her candidacy for a second term in the November election. Horn is chairman of the House Science space subcommittee and has expressed skepticism about aspects of the Artemis program, including NASA’s ability to achieve a landing in 2024.

When a new director would take office is unclear, but experience suggests it may take months after inauguration day. The Obama administration did not appoint Charlie Bolden as administrator (and Garver as deputy administrator) until May 2009; the Senate confirmed them in July. Bridenstine, despite becoming one of NASA’s top contenders for administrator days after Trump’s 2016 election victory, was not nominated until early September 2017.

Morhard, the current deputy administrator, will likely be leaving as well, which he quietly acknowledged in his speech to the SpaceGen summit hours after Biden’s victory. “Things are changing in the United States, we know that,” he said. “I am certainly looking forward to the future and what will follow.”

This article originally appeared in the November 16, 2020 issue of SpaceNews magazine.

[ad_2]

Source link