[ad_1]

The importance of commercial farm animals in the COVID-19 pandemic has received a lot of attention in recent weeks, when a new variant of SARS-CoV-2 was detected in farmed mink. Unfortunately, mink tend to be relatively susceptible to respiratory infections, and these can easily be spread in mink farms due to the high housing density.

Data from the Netherlands at the start of the pandemic revealed that mink can easily be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and then transmit the virus to humans. In Denmark, 214 people have been infected with a variant of SARS-CoV-2 which is presumed to have mutated in Danish mink. More than 200 mink farms have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, and at least five different mink variants of the virus have been detected so far.

These events triggered a mass cull of farmed mink in this country (although this was limited due to legal issues), and shed light on the worrying scenario of human-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2, with potential for the virus to change in mink before re-infecting people.

(AP Photo / Sergei Grits, file)

Specifically, this latest occurrence reveals the possibility that mink could serve as an alternative host to promote SARS-CoV-2 mutations, which can be transmitted to humans and other animals, both domestic and wild and potentially. by placing the wild mustelid (mink, ferrets and related species) at risk.

Bridging the gap between human and animal health

We are researchers in the fields of virology, immunology and pathology. Our research programs link human and animal health and study virus transmission, immune responses to viruses, how viruses cause disease, and the development of strategies such as vaccines to prevent infectious disease. Recent news linking mink to the current pandemic highlights the importance of research at the interface of animal and human health.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has learned a lot about virology, as well as the concept of One Health. At the heart of One Health is the idea that human health and animal health are closely linked in a shared environment and that we need to broaden our perspectives beyond just human health.

Indeed, animals have been at the center of this pandemic from the start. Overwhelming evidence suggests that this coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), which causes COVID-19, originates from bats. There is debate as to whether an animal intermediate host could have harbored additional changes to SARS-CoV-2 to produce the current virus which spreads efficiently from person to person. The main candidate for this is a scaly anteater known as the pangolin.

(AP Photo / Themba Hadebe)

What is known for sure is that changes in coronaviruses can occur over time due to inherent and intentional errors in the ability of these viruses to copy their genetic codes. This allows a virus to make small changes over time and is an efficient way for it to adapt to new environments.

Changes in spike protein

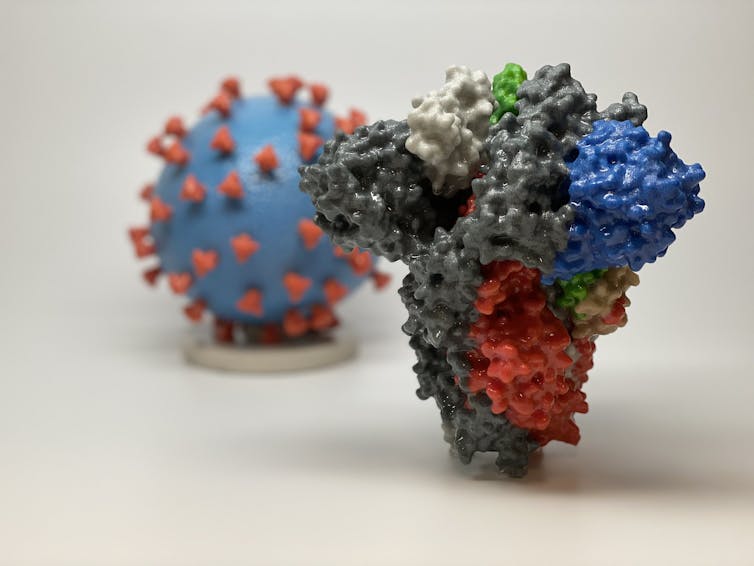

One of the recently identified Danish mink strains is of particular concern because genome changes have occurred in what is known as the virus spike protein, which it uses to enter human cells. These changes have been detected in 12 human cases related to this particular mink variant. Fortunately, this change does not appear to correlate with worse clinical outcomes, based on a small number of cases.

The spike protein is also the primary target of natural and vaccine-induced immune responses to the virus. In theory, if SARS-CoV-2 mutates too much, the immunity derived from the parental virus, acquired either by natural infection or by vaccination, could become less effective against the new strain.

NIH, CC BY

The good news is that, so far, there is no evidence that the mink-derived SARS-CoV-2 mutant can bypass natural or vaccine-induced immunity. Fortunately, our immune systems are designed to generate antibodies against several parts of the spike protein. This means that if only a small part of the spike protein is mutated, the antibodies against other parts of the protein should still confer at least some protection.

Ready-to-use vaccine technology

The fact that SARS-CoV-2 can change highlights the need for vaccines that not only induce protective antibodies, but that can also trigger robust T cell responses, which is the other major mechanism by which our immune system can. kill viruses. Like antibodies, T cells will target multiple parts of viral proteins, thereby increasing the chances of maintaining immunity against unmutated regions of proteins.

It might also be important to consider making vaccines that target more than one of the SARS-CoV-2 proteins. It is very difficult for a virus to make major changes to several proteins without compromising its physical form.

Read more: Training our immune systems: Why we should insist on a high-quality COVID-19 vaccine

The other issue that SARS-CoV-2 mink brings to the forefront of vaccine development efforts is the need for “plug-and-play” vaccines. These are vaccine technologies in which the viral protein that the vaccine is designed to target can be easily exchanged for a different version of the viral protein.

Once approved by health regulators as safe and effective against a highly pathogenic coronavirus, these technologies could, in theory, be rapidly modified to target emerging mutant viruses; Similar to the annual influenza vaccine which is modified annually to target emerging variants of the influenza virus.

Address threats and manage health

As mink has only recently been confirmed as a possible reservoir for SARS-CoV-2, more research is urgently needed to inform rational decisions to slaughter millions of these animals. Even if mass culling continues, mink farms are unlikely to be completely phased out globally in the near future. The question then is how to manage the potential threat to human health of SARS-CoV-2 in mink in the long term?

First, improved biosecurity measures should be implemented in mink farms.

THE CANADIAN PRESS / Geoff Robins

Second, farmed mink coronavirus testing should be added to the surveillance programs of animal health regulatory agencies, as this information is made available to human health regulatory authorities.

Third, consideration could be given to adapting COVID-19 vaccines to animal reservoirs, which would now include farmed mink. These recommendations would not only reduce the potential spread of coronaviruses from mink to humans, they would simultaneously address the health issues related to SARS-CoV-2 in mink. This is because mink can develop COVID-19 after being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and it can sometimes be serious and fatal, without effective current treatment.

Unless future evidence suggests otherwise, it may be best to stay the course with current vaccine development programs in an effort to gain approval from multiple technology platforms for use in humans. Then these platforms can be easily modified, like the annual influenza vaccine, to target emerging mutant viruses, if necessary.

At the same time, public health agencies interested in promoting human health should broaden their visions to include the health and surveillance of domestic animals and wildlife at the interface point between human and veterinary medicine.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, humans are currently the largest reservoir of virus on Earth, and the threat of human hosts spillover onto farm animals and wildlife is now evident. Now is the time to take stock of our relationships with animals and the natural world and take action to ensure health for all and this biosphere we share.

[ad_2]

Source link