[ad_1]

Access to adequate housing and shelter is a basic human right, considered essential to human well-being through the provision of essential facilities for safety, comfort, health and nutrition . However, large inequalities persist and a third of the world's urban population lived in shanty towns in 20141. In response, Sustainable Development Goal 11 aims to ensure universal access to adequate, safe and affordable housing and to improve slum upgrading by 2030.2. This goal is based on Goal 7 of the Millennium Development Goals, which aimed to significantly improve the lives of 100 million people living in shantytowns by 2020.3.

The opportunity and the need to improve housing are particularly pressing in Africa, with its rapidly changing economic and demographic profile. The continent's population is experiencing the fastest growth in the world and is expected to grow from 1.2 billion in 2015 to 2.5 billion by 2050 (an increase equivalent to the current population of India).4which will require hundreds of millions of new homes. Alongside the growing demand for housing, the existing housing stock is gradually changing – for example, thatched roofs are replaced by corrugated iron roofs, and the earthen walls by concrete and brick walls.5. These changes represent an excellent opportunity to improve human well-being. They also reflect the urgent need to invest in housing infrastructure so that vulnerable people are not left behind6.

Reliable measures of housing types in Africa are essential for tracking changes and targeting interventions, but existing data on housing in Africa are limited7. The main indicator related to the Millennium Development Goals and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for housing is the prevalence of urban slums, whose estimates are limited to urban areas only, derived from extrapolations of based on national survey data, limited to specific years the continent at any sub-national scale8.9. Other detailed records on housing conditions in Africa focus on housing costs and financesten. Here we carry out a standardized analysis using a geospatial framework to quantify the changing housing profile in urban and rural sub-Saharan Africa at the time of the Millennium Development Goals. We show that housing in Africa has undergone a marked change between 2000 and 2015, but that housing is still not improved.

To quantify housing changes in sub-Saharan Africa, we used 62 national georeferenced household surveys, representing 661,945 unique households in 31 countries (Extended Data Fig. 1). We designed a geostatistical regression model to map the building materials of a house and the type of house as a whole at a distance of 5 × 5 km.2 resolution across sub-Saharan Africa. We classified home building materials in a binary variable comparing homes constructed from finished materials (eg, parquet, vinyl, tile, cement or carpet) to those built from natural or unfinished materials (earth, sand, dung or palm, for example). floor coverings) (extended data table 1). We have based our classification of housing type on the definition of slum habitat in the Millennium Development Goals and Sustainable Development Goals. We considered that "unimproved" dwellings had at least one of four characteristics: (1) unimproved water supply; (2) unimproved sanitation; (3) more than three people per room; and (4) home made of natural or unfinished materials (additional methods). We considered homes with none of these "enhanced" features.

The independent variables (covariates) used in our model were aridity11, urbanity12accessibility13, displacement friction13, night lights14 and irrigation15, which are commonly used in geostatistical models centered on Africa16; we also included space and time to account for residual autocorrelated effects. Our geostatistical model uses the approach of random Fourier features17 wherein a nonlinear interaction function is defined through large feature spaces computed in explicit form in a feature map. The feature map that characterizes this relationship ( left ( varphi: { mathscr {X}} to { mathscr {H}} right) ) induces a measure of similarity – the function of the kernel ( left (k: { mathscr {X}} times { mathscr {X}} to { mathbb {R}} right) )-such as (k left ({x} _ {i}, {x} _ {j} right) = { left ( varphi left ({x} _ {i} right {x} _ {j} right) right)} _ {{ mathscr {H}}} ). Expand a previous study17, our characteristic map takes the spectral form of Fourier (z (x | omega) = {[{rm{c}}{rm{o}}{rm{s}}({x}^{T}omega ){rm{s}}{rm{i}}{rm{n}}({x}^{T}omega )]} ^ {T} )such as (k left ({x} _ {i}, {x} _ {j} | theta right) approx frac {{ sigma} ^ {2}} {{N} _ {{ rm {feat}}} { sum} _ {r = 1} ^ {M} z { left ({x} _ {i} | { omega} _ {r} right)} ^ {T} z ({x} _ {j} | { omega} _ {r}) ), with spectral measurement ωr. Rather than assuming a specific spectral distribution ωr, we get this Lebesgue measure directly from the data18. Given a response variable (for example, wall material), we used a beta-binomial likelihood function p([[[[there+, theretotal]| X, ω, φ) = BetaBinomial (z(X|ω) φ) that allowed overdispersion in the data while simultaneously taking into account the variation in sample size (from theretotaltheretotal). We performed the regularization with the help of dropouts19. The approximate posterior confidence intervals were estimated using the weighted likelihood bootstrap.20. The adjustment was performed using a stochastic gradient descent ADAM21. Cross-validation was performed to verify the fit of the model and to evaluate the predictive accuracy of the model (additional text, extended data, Figures 2 and 9). The population-weighted prevalence of people living in different types of housing in urban and rural areas was calculated using the annual demographic data of the WorldPop project.22 and a static urban-rural definition of the overall urban footprint project23.

Our analysis revealed a marked housing transformation in Sub-Saharan Africa from 2000 to 2015. In all sub-Saharan African countries (excluding South Africa, Comoros and desert areas), the prevalence of houses built with finished materials increased from 32% (29-33%) in 2000 to 51% (49-54%) in 2015 (Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2). Our analysis suggests a generalized pattern of incremental changes to the roof, then the walls and finally the floor of houses (Extended Data Fig. 3). Overall, the projected prevalence of improved housing (with improved water and sanitation, sufficient living space and sustainable buildings) doubled from 11% (10-12%) in 2000 to 23% (21-25%) in 2015 (Table 1), with prevalence ranging from 5% (5-6%) in rural Ethiopia to 76% (71-80%) in urban areas of Zimbabwe in 2015 (Supplementary Table 1). Between 2000 and 2015, 134 (118-147) million Africans in the countries analyzed had access to improved housing. However, unacceptable inequalities persist, with 53 (50-57) million urban dwellers (47% (44-50%) of the total urban population of sub-Saharan Africa analyzed) and 595 (585-607) million inhabitants rural areas (82%). (80-83%) of the rural population) living in unimproved housing in 2015.

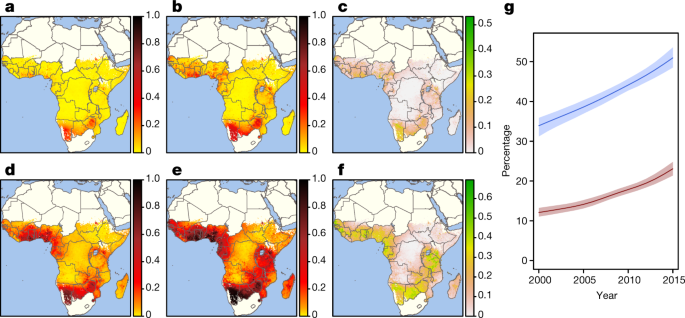

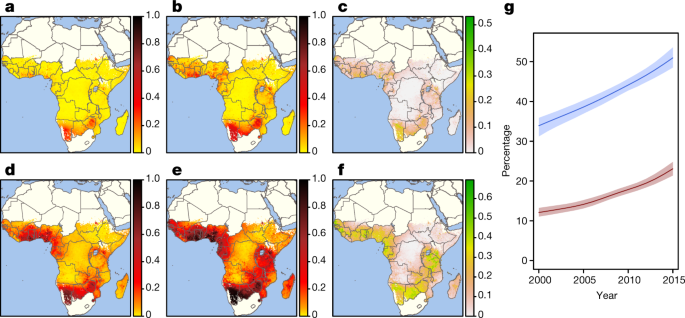

a, Prevalence of improved housing in sub-Saharan Africa in 2000 estimated at 5 × 5 km2 resolution. b, Prevalence of housing improvement in 2015 forecast at 5 × 5 km2 resolution. c, Absolute difference in the prevalence of improved housing in 2000 and 2015. re, The prevalence of houses built with finished materials in 2000 is estimated at 5 × 5 km2 resolution. e, Prevalence of houses built with finished materials in 2015 estimated at 5 × 5 km2 resolution. FAbsolute difference in prevalence of houses built with finished materials in 2000 and 2015. g, Increase in the prevalence of improved housing (red line, shading, 95% confidence intervals) and dwellings constructed with finished materials (blue line) from 2000 to 2015. The results are derived from a geospatial model adapted to 62 surveys representing 661,945 households building materials) and 59 surveys representing 629,298 households (type of house). Houses were classified as improved if they had all of the following characteristics: improved water supply, improved sanitation, three or fewer people per bedroom and finished materials house (extended data table 1 and additional methods). The maps were produced using the raster package (version 2.6-7) in R. The images were plotted using the rasterVis (version 3.4) package.

a, b, The graphs show the weighted average prevalence of the population of houses built with finished materials (a) and housing improvement (b). The bars represent each country in 2000 (purple) and in 2015 (purple and green combined). Houses were classified as improved if they had all of the following characteristics: improved water supply, improved sanitation, three or fewer people per bedroom and finished materials house (extended data table 1 and additional methods). CAR, Central African Republic; Congo, Republic of Congo; DRC, Democratic Republic of Congo.

To examine the links between housing and socio-economic factors, we quantified the association between housing type and household characteristics in 51 national surveys, representing 588,892 households (Complementary Table 2). For each survey, taking into account cluster variation, we jointly estimated the odds of improving housing relative to the householder's level of education, household wealth, and household size. Age of the head of the household. We found that the odds of improving housing were 80% higher in more educated households (adjusted odds ratio, 1.80, 95% confidence interval, 1.68 to 1.93; P <0.001; Fig. 3a), more than double the richest households (adjusted odds ratio, 2.53, 95% confidence interval, 2.28 to 2.82; P <0.001; Fig. 3b) and 31% higher with the age of the household head (adjusted odds ratio, 1.31, 95% confidence interval, 1.24 to 1.39, extended data, Fig. 4). We also observed a higher prevalence of improved housing in urban survey clusters compared to rural survey clusters (Extended Data Fig. 5). In all surveys, a 10% increase in the prevalence of urban clusters (including small rural village-born cities, which accounted for much of sub-Saharan Africa's urban growth) was associated with an increase of 7%. , 5% of improved housing (Extended Data Fig. 6).

a, Association between type of home and level of education. The group increase in the chances of living in an improved home when the head of household said to have completed more than primary education, compared to primary education or less, is indicated by the diamond and the the dotted red vertical line. The continuous blue vertical line represents the null value (no difference between groups). Odds ratios (ORs) are adjusted according to the wealth index, the age of the head of household and the geographical group. The error bars indicate the 95% confidence intervals. b, Association between the type of house and the wealth of the household. The combined increase in odds of living in an improved household among wealth quartile households above 75% compared to all other households is shown. The odds ratios are adjusted according to the level of education, the age of the head of household and the geographical group. Data come from 48 Demographic and Health Surveys, two Malaria Indicator Surveys and an AIDS Indicator Survey conducted between 1996 and 2015 (companion table 2).

Here, we quantified housing conditions in urban and rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa at the time of the Millennium Development Goals and provided a detailed baseline measure for the Sustainable Development Goals. By applying a geospatial approach to empirical observations, we have relied heavily on existing housing measures in Africa, which are limited to urban areas, are not standardized at any subnational level and are derived from more simplistic extrapolations from of survey data. We show that the prevalence of improved housing (defined as housing with improved water and sanitation, sufficient living space, and sustainable construction) doubled between 2000 and 2015, but that an unacceptable proportion of the population still lives in rural areas. unimproved housing in urban areas.

Our findings are consistent with continental scale changes in Africa, driven by economic growth.24. The increase in household spending has probably encouraged people to invest more in their homes and, indeed, we have seen a clear increase in the prevalence of homes built with finished materials since 2000. In addition, the most changed in countries where the baseline prevalence is highest. The number of upgraded dwellings (Extended Data Fig. 7) and the type of house were clearly associated with household level education, wealth and age of the head of household. In urban areas, changes may have also been caused by the lack of traditional materials and the commodification of housing. In the future, sustained population and urban growth in sub-Saharan Africa could help support housing demand and gradually change housing. "Healthy urbanization" has been recognized as important for maintaining economic productivity and growth24.

Our study has important implications for international goals, which have sought to address housing inequities by dramatically improving the lives of 100 million people living in slums by 2020.3 and universal access to adequate, safe and affordable housing by 20302. We see a significant reduction in the prevalence of unimproved urban dwellings in sub-Saharan Africa from 68% (65% to 71%) in 2000 to 47% (44% to 50%) in 2015, which is similar to the equivalent estimates. of the UN 65% in 2000 and 55% in 201425. However, almost half of Africa's urban population still lives in unimproved conditions, which is partly explained by unimproved generalized sanitation – the most common housing deprivation in 75% (52 out of 69 ) surveys analyzed (Extended Data Fig. 8). These findings underscore the urgent need for governments to improve water and sanitation infrastructure as households continue to spend individually for their homes.

Housing is a central pillar of human security and well-being and is increasingly vital in the context of Africa's urbanization and population growth. For example, the design of the house is an integral part of Sustainable Development Goal 3 through a multitude of health outcomes, including mental health, respiratory disease, soil-transmitted helminths, diarrheal leishmaniasis and malaria.26,27,28. As cities in sub-Saharan Africa develop, luxury housing is growing rapidly in major urban centers, along with the expansion of informal settlements with no infrastructure. based. In addition, investment in formal housing is generally lagging behind urbanization, and major urban growth in the continent is concentrated in small urban centers that have limited capacity to organize construction.6. Meeting the housing needs of a growing population is critical for sustainable urban development, the health and well-being of millions of Africans.29and facilitate faster achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. Our maps provide an essential mechanism for guiding intervention and measuring change.

[ad_2]

Source link