[ad_1]

By

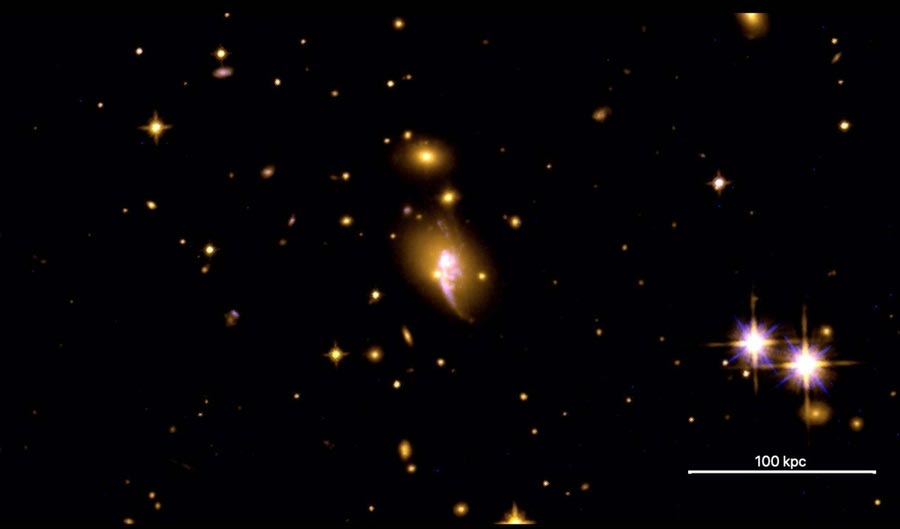

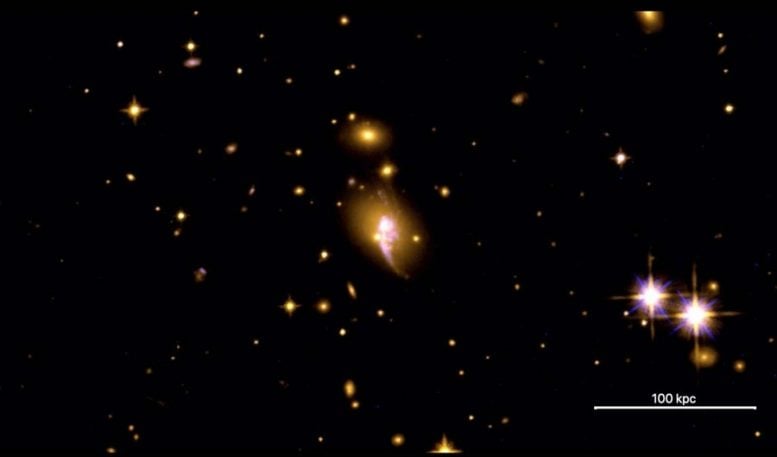

The newly discovered CHIPS1911 + 4455 galaxy cluster has a unique twisted shape compared to other rapidly cooling galaxy clusters. This image was taken with the Hubble Space Telescope. Credit: NASA / ESA / Hubble Heritage Team

According to the researchers, the lessons learned from the CHiPS survey should inform future cluster research.

WITH astronomers have discovered new and unusual galactic neighborhoods that previous studies ignored. Their results, published on March 26, 2021, in The astrophysical journal, suggest that about 1% of galaxy clusters appear atypical and can be easily mistakenly identified as a single bright galaxy. As researchers launch new cluster-hunting telescopes, they must heed these findings or risk having an incomplete picture of the universe.

Clusters of galaxies contain hundreds to thousands of galaxies linked together by gravity. They move through a hot soup of gas called the intracluster medium, which contains more mass than all the stars of all the galaxies within. This hot gas fuels star formation by cooling and emits x-rays that we can observe with space telescopes.

This bright cloud of gas creates a hazy halo of X-rays around galaxy clusters, distinguishing them from more discrete point sources of X-rays produced, for example, by a star or a quasar. However, some galactic neighborhoods are breaking that mold, as MIT Associate Professor Michael McDonald learned nine years ago.

In 2012, McDonald’s discovered a cluster like no other, which glowed like a point source in x-rays. Its central galaxy is home to a starving black hole which consumes matter and spits out X-rays so bright that they cover the diffuse radiation of the intracluster medium. In its core, the cluster forms stars at a rate about 500 times higher than most other clusters, giving it the blue glow of a young population of stars instead of the red tint typical of aging stars. .

“We’ve been looking for a system like this for decades,” McDonald says of the Phoenix cluster. And yet, it had been observed and passed years before, assumed to be a single galaxy instead of a cluster. “It had been in the archives for decades and no one saw it. They were looking past because it didn’t look right.

And so, McDonald wondered, what other unusual groups might be lurking in the archives, waiting to be found? This is how the Clusters Hiding in Plain Sight (CHiPS) survey was born.

McDonald’s Lab graduate student Taweewat Somboonpanyakul has devoted his entire doctorate to the CHiPS investigation. He began by selecting potential cluster candidates from decades of x-ray observations. He used existing data from ground-based telescopes in Hawaii and New Mexico, and visited Magellan telescopes in Chile to take pictures. new images of the remaining sources, looking for neighboring galaxies that would reveal a cluster. In the most promising cases, it has zoomed in with higher resolution telescopes such as the Chandra X-Ray space observatory and The Hubble Space Telescope.

After six years, the CHiPS investigation is now complete. Recently in The astrophysical journal, Somboonpanyakul released the cumulative results of the investigation, which include the discovery of three new galaxy clusters. One of these groups, CHIPS1911 + 4455, is similar to the fast star-forming Phoenix cluster and was described in an article in January Letters from the astrophysical journal. This is an exciting discovery since astronomers only know of a few other Phoenix-type clusters. This cluster invites further study, however, as it has a twisted shape with two extended arms, while all other rapidly cooling clusters are circular. Researchers believe it may have collided with a smaller cluster of galaxies. “It’s super unique compared to all the galaxy clusters we know of now,” says Somboonpanyakul.

In total, the CHiPS survey found that old x-ray surveys missed about 1 percent of galactic neighborhoods because they looked different from the typical cluster. This can have important implications, as astronomers study galaxy clusters to learn more about how the universe expands and evolves. “We have to find all the clusters to get it right,” says McDonald. “Ninety-nine percent completion is not enough if you want to push back the border.”

As scientists discover and further study these unusual galaxy clusters, they can better understand how they fit into the larger cosmic picture. At this point, they don’t know if a small number of clusters are still in this odd, Phoenix-like state, or if perhaps this is a typical phase that all clusters go through for a short period of time. time – about 20 million years, a fleeting moment by space-time standards. It’s hard for astronomers to tell the difference, as they only get one snapshot of each near-frozen cluster. But with more data, they can make better models of the physics governing these galactic neighborhoods.

The conclusion of the CHiPS survey coincides with the launch of a new x-ray telescope, eROSITA, which aims to grow our cluster catalog from a few hundred to tens of thousands. But unless they change the way they search for these clusters, they’ll be missing hundreds that deviate from the norm. “The people who are developing the cluster research for this new x-ray telescope should be aware of this work,” says McDonald. “If you miss 1% of the clusters, there is a fundamental limit to your understanding of the universe.”

Reference: “The Clusters Hiding in Plain Sight (CHiPS) Survey: Complete Sample of Extreme BCG Clusters” by Taweewat Somboonpanyakul, Michael McDonald, Massimo Gaspari, Brian Stalder and Antony A. Stark, March 26, 2021, The astrophysical journal.

DOI: 10.3847 / 1538-4357 / abe1bc

This research was supported, in part, by the Kavli Research Investment Fund at MIT, and by NASA through the Guest Observer programs for the Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Hubble Space Telescope.

[ad_2]

Source link