[ad_1]

The bottom of the sea can be a gaseous place. Underwater volcanoes and the vents spit carbon dioxide (CO2) near the crevices where the tectonic plates separate. Hungry bacteria convert creatures from decomposing depths into natural methane. In addition, new Japanese research reminds us that huge reservoirs of greenhouse gases, of a width of several kilometers, hide in intact pockets just under the seabed.

In a study published August 19 in the newspaper Geophysical Research Letters, a team of researchers discovered one of these pockets at the bottom of the Okinawa Trench, a huge submarine basin located in southwestern Japan, where the plate of the Philippine Sea slowly sinks under the Eurasian plate . Using seismic waves to map the structure of the basin, the team discovered a large gas pocket with a minimum width of 4 km that could contain more than 100 million tonnes (90.7 million tonnes) of CO2, methane or a combination of both. .

Depending on its content, this massive reservoir of seabed gas could represent an untapped source of natural gas, or a time bomb of greenhouse gas emissions The researchers wrote: they only ask to go to the surface.

"If the gas is supposed to be everything CO2, I would say very roughly 50 million tons,[45 million metric tons]"This amount corresponds to an order similar to the annual CO2 emissions of all passenger cars in Japan," Takeshi Tsuji, of the International Institute for Research on Carbon Neutral Energy in Japan, told Live Science, from Kyushu University. about 100 million tons [907 million metric tons] per year)."

In the new study, Tsuji and his colleagues crossed the central part of the bowl and then used a compressed air gun to generate seismic waves from different angles. By measuring the evolution of these waves during their passage in the seabed, the team created an approximate profile of the world hidden under the seabed.

"Seismic pressure waves generally propagate more slowly in gases than in solids," co-authored Andri Hendriyana, another researcher at the International Institute for Research on Carbon Neutral Energies, said in a statement. "Thus, by estimating the velocity of seismic pressure waves across the ground, we can identify underground gas reservoirs and even obtain information about their saturation."

The velocity of the pressure waves has slowed considerably over a large area in the middle of the trough, indicating a massive gas pocket. The team estimated the pocket width but was unable to calculate the depth or concentration of the tank.

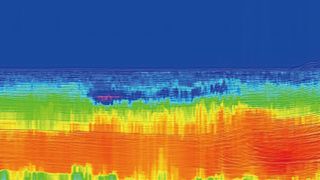

On this seismic velocity map, the long blue-blue patch in the green section represents a vast reservoir of greenhouse gases trapped beneath the seabed.

(Image credit: Takeshi Tsuji, Kyushu University)

With the current data, they could not determine whether the gas in question was CO2 or methane (two gases that are abundant in deep water), which makes the implications of the discovery a bit unclear at the moment.

"On the one hand, if it's methane, it could be an important resource," Tsuji said. (Methane, the main component of natural gas, is used as fuel around the world.) "However, methane is also an important gas for climate change."

After CO2, methane is the second most common heat capture gas in the Earth's atmosphere and accounts for about 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. according to the agency of environmental protection. Concentrations of methane in the atmosphere have skyrocketed by nearly 150% over the past 250 years, NASA reports, and these numbers will likely continue to increase as global warming continues to release methane once trapped in Arctic permafrost.

However, if the gas in the submarine reservoir is mainly CO2, it could have an even greater impact on climate change. If the pocket were to emit and release 50 million tonnes (45 million tonnes) of CO2 into the air at the same time, this could have a measurable effect on CO2 concentrations in the atmosphereand so on climate change. If pockets like this are a common feature of oceanic dissensions, as the researchers suspect, the potential consequences could be even greater.

For the moment, however, there is simply not enough data to draw specific conclusions about what's in the tank, where it comes from and what's in it. It will happen. Further study of the Okinawa Bowl and other offshore rift sites will be essential in determining who (or what) handled the mysterious gas – and who should handle it next.

Originally published on Science live.

[ad_2]

Source link