[ad_1]

The kelp forest that only eight years ago formed a leafy ocean canopy along California’s northern coast has almost completely disappeared, and scientists who study kelp and the species that depend on it are worried about its inability to bounce.

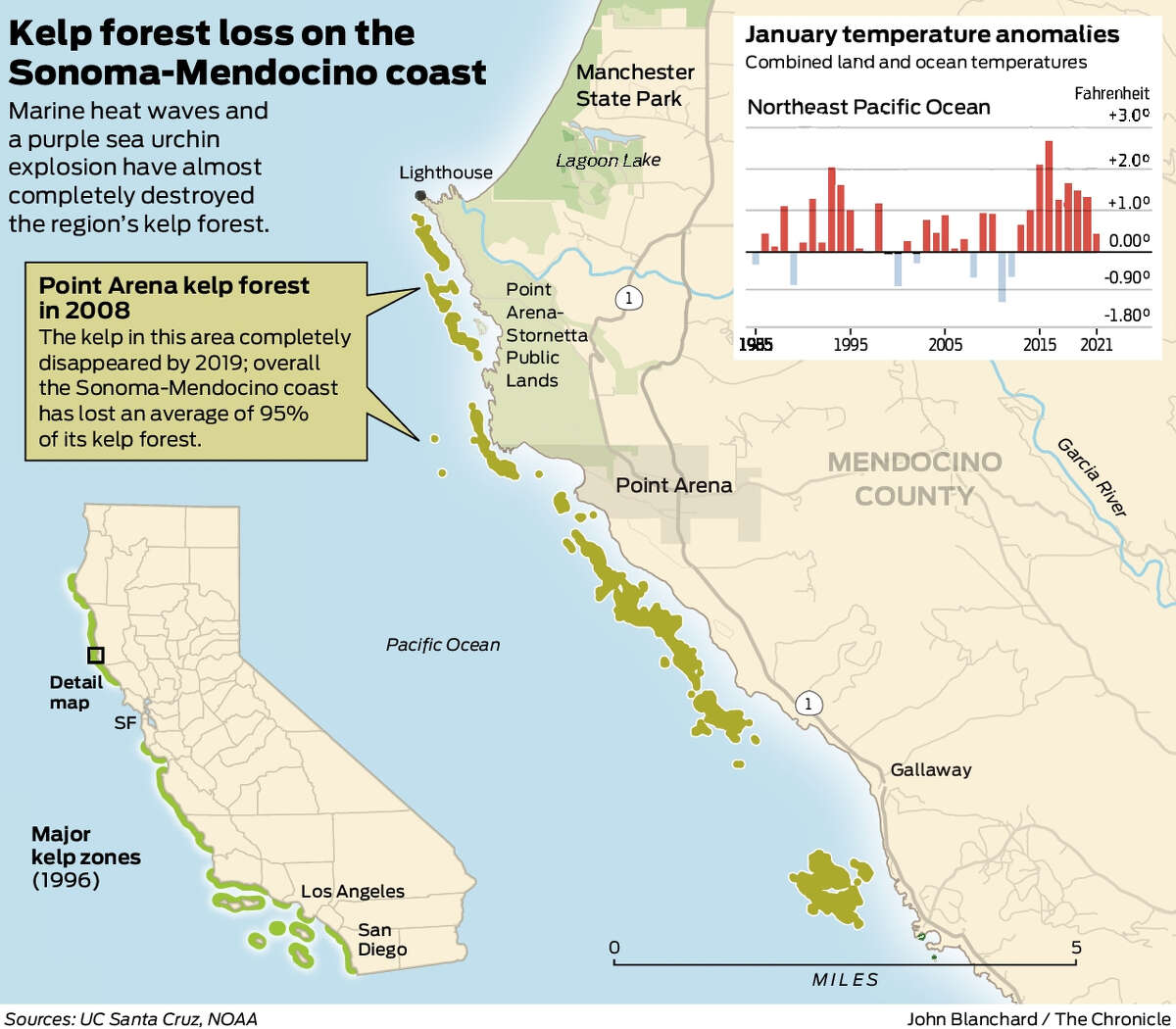

A new study from UC Santa Cruz has found that the kelp forest on the Sonoma and Mendocino coast has declined by an average of 95% since 2013. It analyzed satellite imagery dating back to 1985 to study how a range of factors led to the abrupt kelp forest. decline, including an explosion in the population of purple sea urchins, which eats them, and two waves of marine heat. Research shows the unprecedented destruction was linked to the unusual warming of the ocean, and the kelp forest is unlikely to recover anytime soon, in part because it’s so difficult to remove sea urchins.

“They can actually survive in conditions of starvation,” said Meredith McPherson, a graduate student in the Department of Ocean Sciences at UC Santa Cruz and co-author of the study. “The impact has been that basically there’s no kelp forest anymore, really.”

Bull kelp (Nereocystis as a list) generally thrives in the rocky coastal areas of Sonoma and Mendocino counties and provides habitat for many types of fish and invertebrates, including abalone, sea urchin, jellyfish and sea snails. Also had an impact on local tourism and other businesses – the abalone fishery was closed to recreational divers in 2018 and the commercial red sea urchin fishery in Mendocino County is almost completely closed.

kelp0305_GR

The two hot water episodes that contributed to the decline of the kelp forest include an El Niño and what is known as a “drop” of hot water that lasted together from 2014 to 2016. Roughly the same At the moment, a debilitating disease struck the sunflower starfish population, leaving the purple sea urchin predatorless.

These sea urchins quickly took over, eating the leftover kelp and starving two other species popular with divers and sushi enthusiasts – red abalone and red sea urchin (purple sea urchins are not as commercially viable). What remains is called sea urchin moors, rocky areas completely covered in spiky purple invertebrates for hundreds of miles of the north coast.

“What we are seeing in northern California is unprecedented in terms of its scale,” said Tristin McHugh, kelp project manager at Nature Conservancy’s California Oceans Program, which is developing pilot methods to eliminate purple sea urchins and restore the kelp.

Although there were fears that another drop of hot water would form off Alaska last year, water temperatures on the north coast have returned to normal, McPherson said , and yet the bull’s kelp did not recover. Unlike other kelp native to California, it is an annual species that dies in winter, when it washes off the shore in heaps that look like long green-brown pipes with bulbous ends. It normally goes to each spring.

Scientists had already been monitoring the decline of the kelp forest for years with aerial photographs and tidal data, but the new study was the first to use satellite imagery to more closely analyze changes in growth as well as ocean temperature and nutrient levels.

“We are able to see kelp relatively easily from space using the satellite,” McPherson said.

The growth of bull kelp depends on the cold spring water upwelling that brings nutrients to the surface, and these are reduced when the water temperature rises. While previous El Niño events – a natural pattern that causes the temperature of Pacific water to rise for a year or two – also caused the kelp to decline, it has generally recovered.

Farmed sea urchin from the Norwegian company Urchinomics, which is opening a sea urchin ranch in Bodega Bay.

UrchinomicsWhat was different in 2014-2016 was the explosion of the Purple Sea Urchin and the addition of the Hot Water Drop, which at its peak increased ocean temperatures by almost 7 degrees above average. While there is some evidence that gout was linked to climate change, what is more important is that marine heatwaves are becoming more frequent and intense as global temperatures rise due to the climate change, McPherson said.

Climate change, pollution, and other factors are also responsible for the global decline of kelp forests over the past 20 years, but in California it’s at its worst on the north coast of San Francisco. Monterey Bay and other parts of central California have also lost the kelp forest to sea urchin barrens, but these areas have a mix of bull kelp and giant kelp and also have sea otters that help tackle sea urchins. In southern California, where giant kelp is the main species, the forest has persisted better.

The most concerning part of the decline of the Sonoma-Mendocino kelp forest is that unless the sunflower starfish or other predator returns, the purple sea urchin shows no signs of budding.

“Usually some sort of physical disorder or disease would wipe out the population,” McPherson said. “It could go on for decades and decades.”

The loss of their habitat by purple sea urchins is why the California Department of Fisheries and Wildlife in 2018 put a five-year hiatus on recreational red abalone fishing, which typically brings in recreational divers. from all over California to the North Coast. As a result, the last dive shop in the area closed in Fort Bragg about a year ago.

Many professional and jobless red sea urchin divers have been hired into a state-sponsored program operated by non-profit organization Reef Check to manually remove purple sea urchins from the seabed. It is a slow process. In some cases, there are as many as 20 to 30 sea urchins per square meter of seabed, and similar efforts in Norway, Japan and New Zealand have shown that it is necessary to go down to 2 per square meter to May the kelp forest recover, McHugh mentioned.

She added that the private sector must get involved if there is a long-term solution. It’s starting to happen. Norwegian firm Urchinomics signed a partnership with the owners of Bodega Bay last year to build a sea urchin “ranch”, where purple sea urchins harvested from the coast will be fattened for sale to restaurants and shops.

The Nature Conservancy is also working on pilot programs to see if traps could be used to capture sea urchins and is in talks to build an experimental kelp farm in Humboldt Bay this spring, McHugh said.

McPherson said there were other efforts that are giving the situation some hope, such as developing spore banks so that the kelp can eventually be replanted when the conditions are right.

“It’s a little dark for the north coast,” she says. “But there is a lot of work in the area to see how we can maintain kelp patches for restoration going forward.”

Tara Duggan is a writer for the San Francisco Chronicle. Email: [email protected] Twitter: @taraduggan

[ad_2]

Source link