[ad_1]

Cryptobenthic fish may seem strange, but they are not so different from you and me. They are vertebrates like us, though their hearts, bones and brains are tiny. But unlike us, they do extremely well two things.

"They are the masters of premature death," Simon Fraser, a postdoctoral researcher at Simon Fraser University, told Earther. "And it's their great contribution to coral reefs."

Indeed, in a study published Thursday in Science, Brandl and his colleagues show that without these tiny fish, those who love death, the reefs would have big problems. In doing so, they helped solve a 200-year-old puzzle called Darwin's paradox, which asks how reefs exist in otherwise desert-like parts of the ocean.

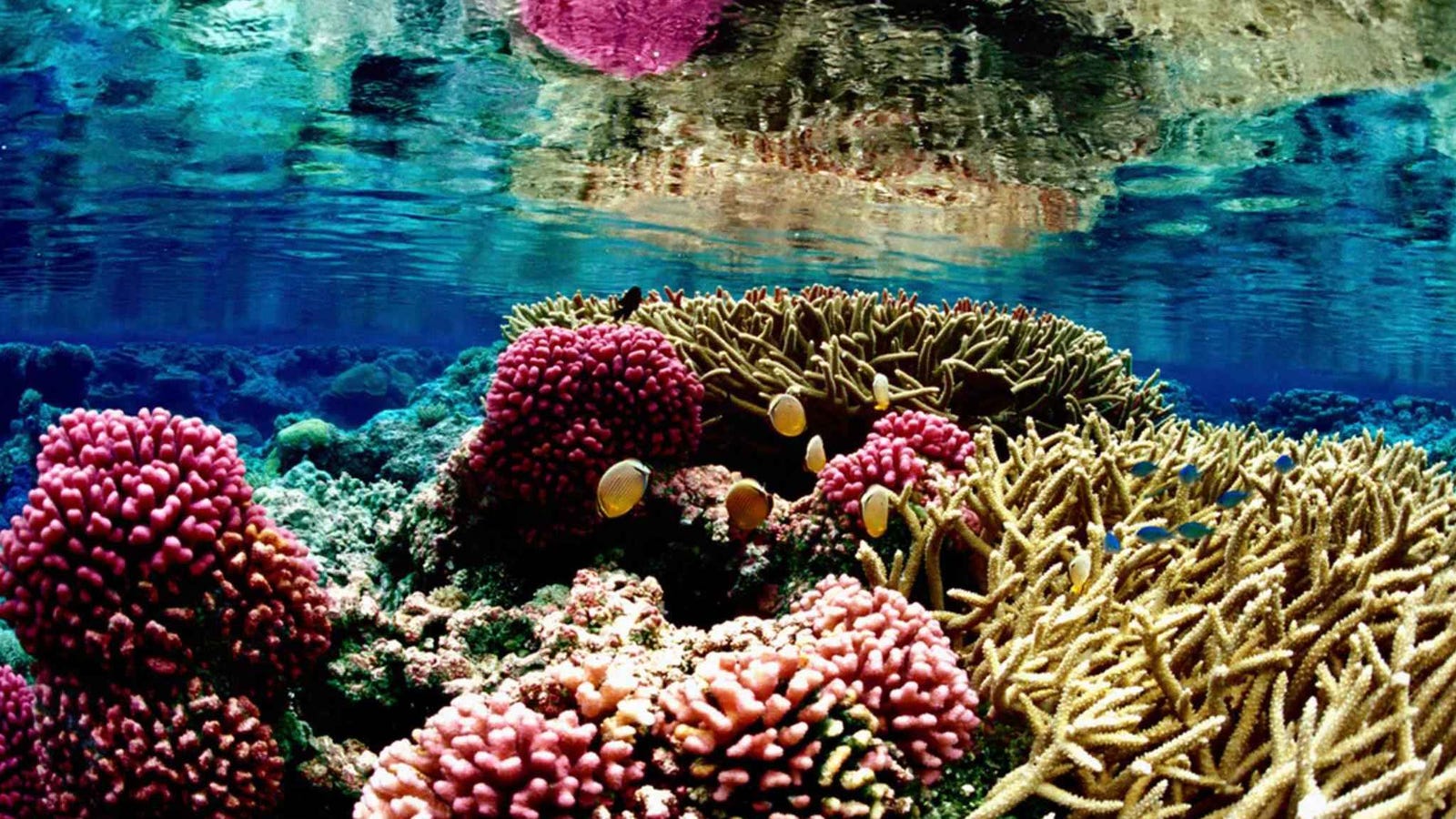

Dive or snorkel on a reef, and you will be forgiven for not noticing the cryptobenthic fish. The group of 17 small swimmers is only about 2 inches in length and spends time in the corners of rough coral surfaces. Of course, they come in shimmering varieties like the other big reef fish, but it's definitely not the tangs of angels, damsels and multicolors that are the stars of the show.

But it turns out that these rinky-dink fish are basically the reason why life blossoms on the reefs. On the surface, it looks like they do not do much, but it's their penchant for death that feeds all the other fish. This tiny fish that feeds the big fish is not really revolutionary, but the new results show that cryptobenthic fish produce an incredible number of larvae to maintain the equilibrium of the food chain. And these larvae give up on a long sea voyage by other baby reef fish – where they would die even more prematurely – allowing more people to come back to replenish the stock on the reef.

Data from various reefs around the world, including Belize, Australia, and French Polynesia, show that almost two-thirds of the larvae come from only 17 types of cryptobenthic fish. These larvae quickly replace adults swallowed by larger fish, allowing cryptobenthes to account for 60% of all fish consumed on a reef. Essentially, they act as a fertilizer that allows reef communities to live in parts of the ocean that would otherwise be barren. The results provide an answer to Darwin's paradox, although other research has also provided further explanations. In any case, the new relationship opens up essential bases for discussing reefs and their conservation.

Nobody fishes these small fish, but they are threatened by other problems such as climate change. Warming waters kill the coral. As corals die and erode, fish lose their habitat, which means that once vibrant reefs could become deserts when the food chain dissolves completely. In terms of biodiversity, it is wise to preserve the reefs and to ensure that small fish continue to have a home. But Brandl pointed out that 500 million people also depend on reefs for fishing and their livelihoods. So, in a way, cryptobenthic fish are also the basis of the reef economy.

Brandl's research is not complete either. He added that the next step was to determine where the larvae were before returning to the reefs, explaining why their survival rate was higher than the larvae of large fish.

"This will help us maintain this cryptobenthic fish conveyor belt that feeds the coral reefs," he said.

[ad_2]

Source link