[ad_1]

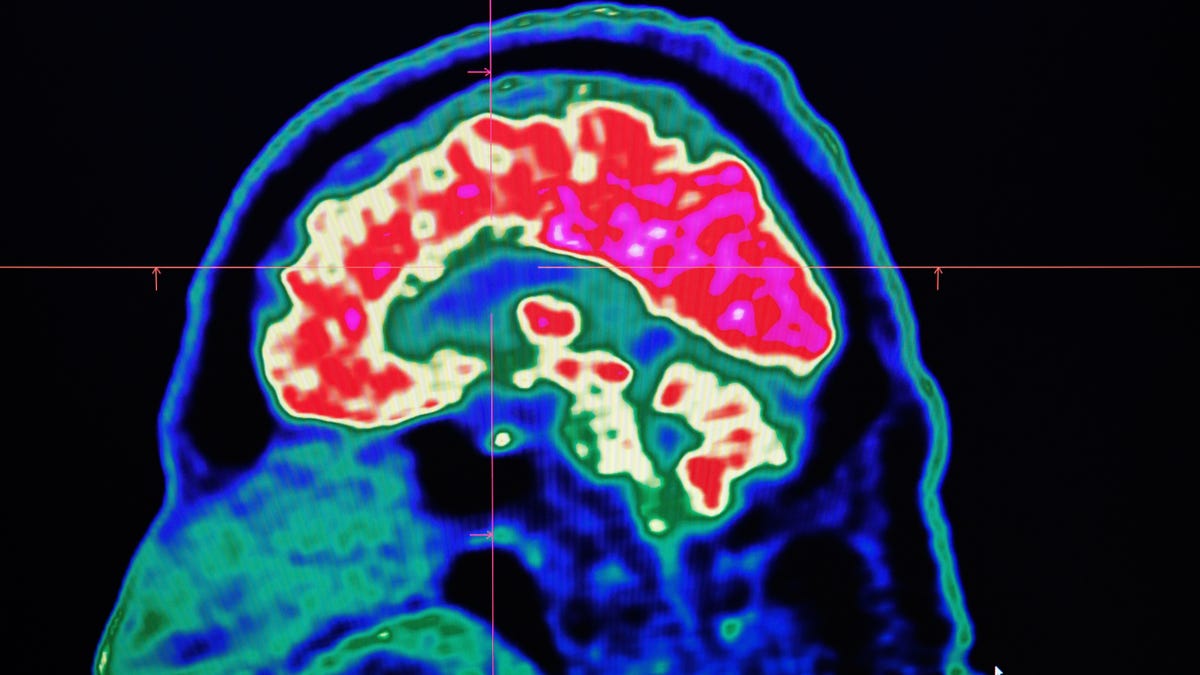

Even after we die, some of our brain cells may experience a momentary last and big burst of life, according to new research released Tuesday. The study found evidence that certain “zombie genes” in our brain cells are active more frequently soon after death, causing some cells to expand dramatically for hours. The results will not radically change our concepts of life and death, but they may have important implications for the study of brain tissue harvested postmortem.

It is no secret that our cells can stay alive and function for a while even after we are clinically dead, before they finally turn off. But although almost every cell carries the same genetic information as the next, different types of cells express this genetic information differently, with various genes being turned on or off. And when researchers looked at the gene expression of different cells inside a “dying brain,” they found distinct patterns.

For their study, published In Scientific Reports on Tuesday, the team looked at brain tissue samples donated by patients who had recently had brain surgery for epilepsy (surgical treatments can safely remove parts of the brain involved in the seizure disorder). They then mimicked the process of brain death by leaving out the freshly collected samples at room temperature for various periods of time, up to 24 hours. All the while, the team was gathering information about the cellular and genetic activity of these cells.

In the majority of the genes they studied, characterized as “housekeeping genes” that maintain basic cellular function, they found that the genes remained at the same level of activity throughout the 24 hour period. In “neuronal” genes, the genes that are ignited in neural cells responsible for brain functions such as thinking and memory, their activity began to drop after 12 hours.

G / O Media can get a commission

But in a third group of genes, linked to glial cell function – the immune and supporting system of the brain – gene expression actually increased after “death” and continued to increase for up to 24 hours. later. The glial cells themselves have also grown massively in size and even grew new “arms” as the neurons in those samples degenerated.

TThe results do not prove that zombies are theoretically possible, aAnd it’s not even really a huge surprise that glial cells are particularly active after death. The cells are probably responding to the injury and inflammation that occurs in the brain when it is deprived of oxygen after someone’s dying moments. But the findings present a potential wrinkle in how much research on the human brain is conducted, the authors say, as many studies rely on postmortem examinations of the brain.

“Most studies assume that everything in the brain shuts down when the heart stops beating, but it doesn’t,” said study author Jeffrey Loeb, head of neurology and science. rehabilitation at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine, in a declaration published by the university. “Our results will be needed to interpret research on human brain tissue. We just haven’t quantified these changes so far. “

One problem is that research into disorders like Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia often depend on the postmortem brain samples that are taken 12 hours or more after dead. If the results here are valid, then many of these studies might miss important clues left inside dying cells that might later disappear. Loeb and his team hope that future studies can better capture the changes that occur in a dying brain. One potential solution, for example, might be to collect brain samples for even earlier post-mortem research or rely more on samples from consenting patients who are undergoing brain surgery anyway.

“The good news from our findings is that we now know which genes and cell types are stable, which degrade and increase over time, so that the results of postmortem brain studies can be better understood,” said Loeb.

[ad_2]

Source link