[ad_1]

Credit: Phil Vandenbossche & Nelson Kuna / CSIRO

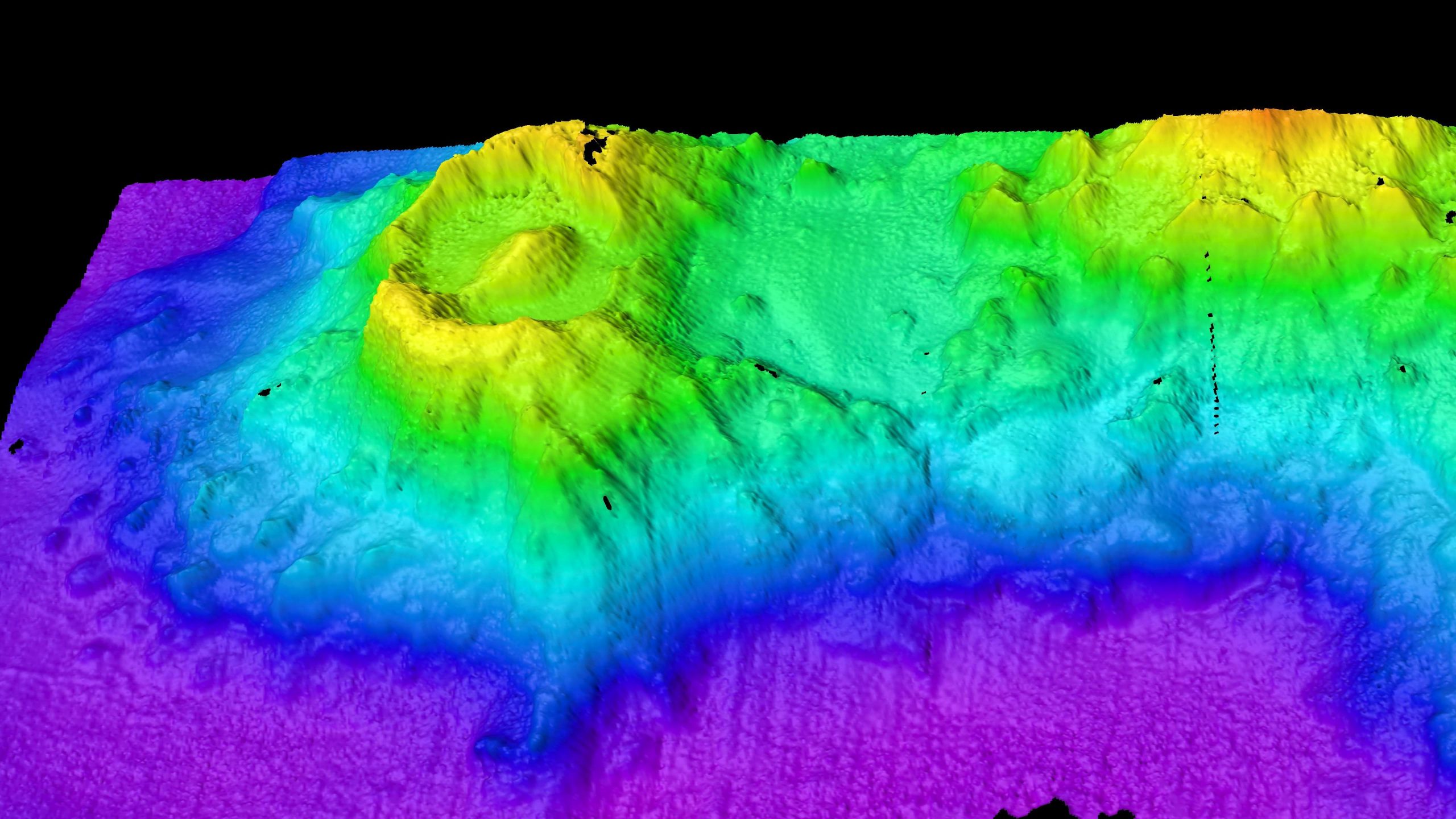

Resembling the Eye of Sauron from the Lord of the Rings trilogy, an ancient underwater volcano was slowly revealed by multibeam sonar 3100 meters below our ship, 280 kilometers southeast of Christmas Island. It was day 12 of our exploration trip to the Australian Indian Ocean Territories, aboard CSIRO’s ocean research vessel, the RV Investigator.

Previously unknown and unimaginable, this volcano has emerged from our screens as a giant oval-shaped depression called a caldera, 6.2 km by 4.8 km in diameter. It is surrounded by a 300 m high ledge (resembling Sauron’s eyelids), and has a conical peak 300 m high in its center (the “pupil”).

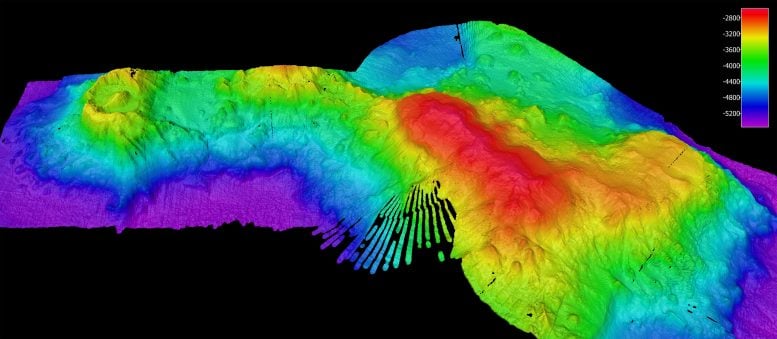

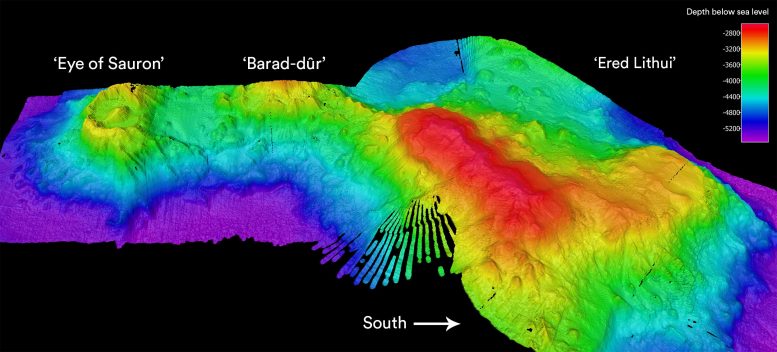

Sonar image of the “Eye of Sauron” volcano and nearby seamounts on the seabed southwest of Christmas Island. Credit: Phil Vandenbossche & Nelson Kuna / CSIRO

A caldera is formed when a volcano collapses. The molten magma at the base of the volcano moves upward, leaving empty chambers. The thin solid crust on the surface of the dome then collapses, creating a large crater-like structure. Often a small new peak will then begin to form in the center as the volcano continues to spew magma.

A well-known caldera is that of Krakatoa in Indonesia, which exploded in 1883, killing tens of thousands of people and leaving only pieces of the mountain’s edge visible above the waves. In 1927, a small volcano, Anak Krakatoa (“child of Krakatoa”), had developed in its center.

In contrast, we may not even be aware of volcanic eruptions when they occur deep under the ocean. One of the few telltale signs is the presence of light pumice rafts floating on the surface of the sea after being blown by an underwater volcano. Eventually, this pumice stone becomes waterlogged and sinks to the bottom of the ocean.

Our volcanic “eye” was not alone. Further mapping to the south revealed a smaller sea mountain covered in numerous volcanic cones, and even further south was a larger, flat-topped seamount. Following our theme of The Lord of the Rings, we have nicknamed them Barad-Dûr (“Dark Fortress”) and Ered Lithui (“Mountains of Ashes”) respectively.

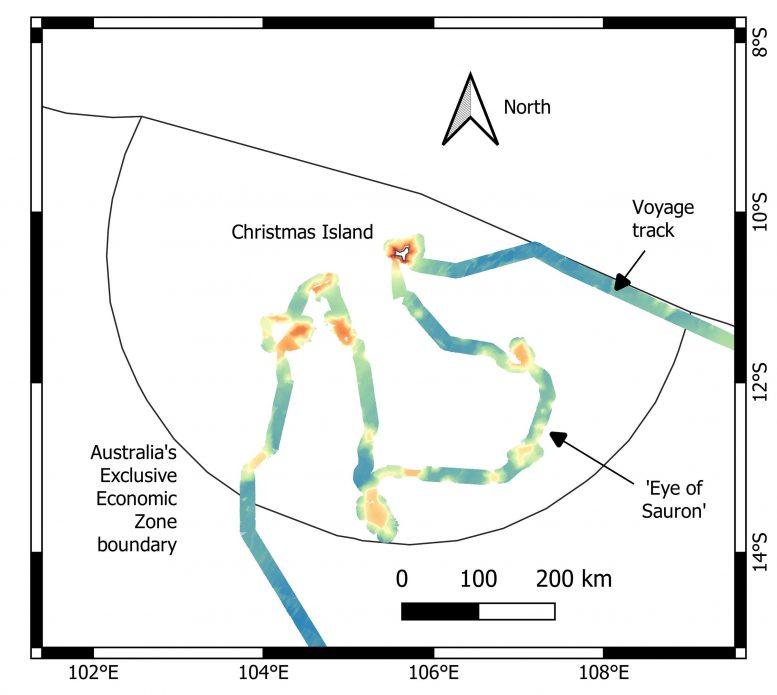

The RV Investigator’s trip around Christmas Island. Credit: Tim O’Hara / Victoria Museums

While author JRR Tolkein’s knowledge of mountain geology is not perfect, our names are wonderfully appropriate given the jagged nature of the former and the pumice-covered surface of the latter.

L ‘Eyeil de Sauron, Barad -ûr and Ered Lithui are part of the Karma Seamount Cluster which was previously estimated by geologists to be over 100 million years old and which formed next to ‘an ancient marine ridge at a time when Australia was located much further south, near Antarctica. Ered Lithui’s flat top was formed by wave erosion as the seamount passed the sea surface, before the heavy seamount slowly descended back down into the soft seabed of the ocean. . The summit of Ered Lithui is now 2.6 km below sea level.

But here is the geological conundrum. Our caldera looks surprisingly cool for a structure that is expected to be over 100 million years old. Ered Lithui has nearly 100m of layers of sand and mud draped over its summit, formed by the sinking of organisms that have died over millions of years. This sedimentation rate would have partially smothered the caldera. Instead, it’s possible that volcanoes continued to sprout or new ones formed long after the original foundation. Our restless Earth is never still.

The large predatory starfish of the deep Zoroaster. Credit: Rob French / Victoria Museums

But life is adapting to these geological changes, and Ered Lithui is now covered with sea-bed animals. Brittle stars, starfish, crabs and worms burrow or skate on the sandy surface. Erect black corals, fan corals, sea whips, sponges and barnacles grow on the exposed rocks. Gelatinous Cusk roams around rocky ravines and boulders. Batfish prey on unsuspecting prey.

Small batfish patrol the summits of seamounts. Credit: Rob French / Victoria Museums

Our mission is to map the seabed and study marine life from these ancient and isolated seascapes. The Australian government recently announced its intention to create two huge marine parks in the regions. Our expedition will provide scientific data that will help Parks Australia manage these areas in the future.

Elasipod sea cucumbers feed on organic detritus on the deep sandy seabed. Credit: Rob French / Victoria Museums

Scientists from museums, universities, CSIRO and the Bush Blitz of Australia are taking part in the trip. We are about to complete the first part of our trip to the Christmas Island area. The second part of our trip to the Cocos (Keeling) Island region will be scheduled for next year.

No doubt many of the animals we find here will be new to science and our earliest records of their existence will come from this region. We expect many more surprising discoveries.

Written by Tim O’Hara, Senior Curator of Marine Invertebrates, Museums Victoria.

Originally posted on The Conversation.![]()

[ad_2]

Source link