[ad_1]

IThat was in 1969. Last year, President Kennedy pledged to put a man on the moon and send him back safely "before the end of this decade." NASA was not sure it could be done on time. There may be only three opportunities left before the deadline expires.

On January 6, Deke Slayton, head of the astronaut office at NASA, called the Apollo 11 crew – Neil Armstrong, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin and Michael Collins – in his Houston, Texas office , and announced to them that their mission for July, could involve a lunar landing. A few weeks earlier, Apollo 8 made its first crewed voyage around the moon and the tasks of the next Apollos 9 and 10 were set. Apollo 9 was supposed to test the lunar landing satellite in Earth orbit and Apollo 10 was a complete rehearsal on the Moon – all but the actual landing.

The crew of Apollo 11 was presented to the press on January 9 and the assembled journalists immediately seized the big question: "Which of you two will be the first man to go out on the lunar surface?

It is clear that during the first few months of 1969, Aldrin thought that he would be the first. He said that he had never really thought about it and that he had naturally assumed that it would be him. Perhaps he was right: NASA's deputy administrator for manned space flights, George E. Mueller, had told several people, including members of the press, that he would make the first impression. .

But the word began to filter that it would be Armstrong. Aldrin was angry: Armstrong was a civilian. It would be an insult to service. He himself was technically still a member of the Air Force, although he has not served for 10 years, so it is to maintain his hours of flight. So he approached Armstrong. Aldrin later wrote (though he claimed that this had been done by his co-author): "He equivocated a minute or two, and then with a coolness that I did not know that". he owned, he said that the decision was historical enough and that he did not want to exclude the possibility of going first. Armstrong then stated that he could not remember the conversation.

Aldrin spoke to colleagues; for some, it was perceived as lobbying behind the scenes. Gene Cernan (the last person to walk on the moon) said, "One day, he came into my office at the Manned Spaceflight Center like an angry stork, loaded with charts, charts, and statistics, claiming that He considered it obvious. he, the lunar module pilot, and not Neil Armstrong, should be the first to descend on Apollo 11. Since I shared an office with Neil Armstrong, who was training this day Here I found Alddr's arguments both shocking and ridiculous. "

It was not so that Aldin saw it. Writing some 40 years later in his book Beautiful DesolationHe stated that during his training in early 1969, he had recognized that the great responsibility lay with him. In all previous missions of Gemini and Apollo, the space sorties were borrowed by the junior officer while the commander remained inside the space capsule. From February 1969, Aldrin maintained this plan. He said he did not solicit support from older astronauts. He simply behaved like a competing air force pilot. "In truth, I did not really want to be the first person to walk on the moon. I knew the media would never leave this person alone. "

On April 14, speculation ended. At a press conference, NASA announced that "the plans provided for Mr. Armstrong to be the first man to go out after landing on the moon, and a few moments later, Colonel Aldrin will follow." Aldrin then asserted that he thought the lunar module layout indicated that Armstrong had to go out first because he was right and that the door was opening towards Aldrin. It was not technically it could have been Aldrin – it was enough for them to change sides before putting on their backpacks.

Later, the flight director, Chris Kraft, explained the thought of NASA. He said that they knew very well that the first man on the moon would be a Charles Lindbergh of modern times. Armstrong was calm, calm and had absolute confidence. He knew that he was of the Lindbergh type. He did not have ego. For his part, Aldrin desperately wanted this honor and did not let him know. Kraft added that no one had criticized Aldrin, but they did not want him to be the ambassador of humanity. "The hatch design did not come in. It was a rationalization, a comfort for Buzz. "

During the first half of 1969, there were times when things did not go as smoothly as NASA would say. When Apollo 10 took off in May for the general rehearsal flight, Armstrong and Aldrin were spending up to 14 hours a day in the Cape Kennedy landing simulator, joining their family in Houston on the weekends. Those around them worried that they would run out and some wondered how long they could go on. Janet Armstrong said that her husband frequently came home with a white face. In June, it was clear that their morale was low. Everyone was wondering if there was enough time to learn everything.

NASA's new administrator, Thomas Paine, was also worried. Before leaving for the Paris Air Show, he asked Apollo Program Director Sam Phillips if he was concerned about the crew. Shortly after, Phillips convened a flight readiness review meeting using teleconferences to find out if he was pushing the crew too far. "I'm quite ready to wait if something is not ready," he said. Charles Berry, director of medical research and operations in Houston, said he was concerned about the crew and would like the mission to be delayed. Deke Slayton, who also defined the duties of the crew, also participated in the conference call. He said that Armstrong had told him that yes, the schedule was tight and that yes, they were exhausted, but the pace would slow down in early July and they would rest at that time. The meeting decided that "Apollo 11 could proceed to the landing and this was announced to the public the next day. Janet Armstrong saw her husband's mood improve.

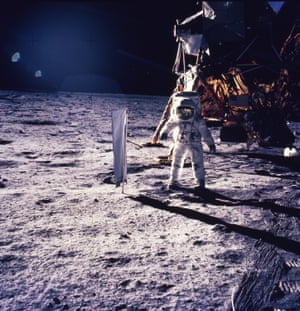

On July 20, they were in lunar orbit. Armstrong and Aldrin entered the lunar module, dubbed Eagle, to deflate and begin the landing. None of them has been in the simulator for about two weeks. After the initial part of the descent, they performed the so-called pitchover maneuver, allowing them for the first time to see the moon below. They did not recognize anything. They were heading towards a large field of blocks, flying on a trajectory that they had never flown in the simulator. Back at Mission Control, capsule communicator Charlie Duke said it was something they had never seen before [Armstrong] At only 400 feet deep, and suddenly, he … the problem recovers and he slows down and then goes back down. . "

It was Armstrong's moment. The biggest test for a pilot in history. He delivered and deserved the first imprint.

• Apollo 11: the inner story by Dr. David Whitehouse is published on June 6th by Icon Books (£ 12.99). To order a copy, go to guardianbookshop.com. UK free p & p on all online orders over £ 15

[ad_2]

Source link