[ad_1]

Comets and asteroids are two types of rocks that hang out in space, but their differences are quite stark.

Comets generally originate from the outer solar system and have long elliptical orbits. They are filled with ice that begins to sublimate as the comet approaches the Sun, generating a dusty and hazy atmosphere (called a coma) and the famous comet tails.

Asteroids typically hang out in the main asteroid belt, between Mars and Jupiter, with orbits that more closely resemble planets. They are also believed to be quite dry and rocky, so they don’t tend to engage in the picturesque outgassing seen in their more exotic relatives.

A newly discovered space rock, however, appears to have characteristics of both. His name is (248370) 2005 QN173, and it hangs around the main asteroid belt, like millions of other asteroids, circling the Sun in a pretty planetary-style quasi-circle.

But, like a comet, in July of this year 248370 was spotted showing signs of outgassing on its closest approach to the Sun (perihelion) and a long comet tail. That would make it a rare hybrid of the two – a type of object that we call an active asteroid or a main belt comet.

It is one of some 20 such rarely seen objects – among the more than 500,000 known Main Belt objects – that have been suspected to be Main Belt comets, and only the eighth such object. has been confirmed. In addition, astronomers have discovered that the object has been active more than once.

“This behavior strongly indicates that its activity is due to the sublimation of icy matter,” said astronomer Henry Hsieh of the Planetary Science Institute.

“248370 can be thought of as both an asteroid and a comet, or more precisely, a main belt asteroid that has just been recognized as a comet as well. It fits the physical definitions of a comet, in that sense. that it’s probably icy and throwing dust into space, even though it also has the orbit of an asteroid.

“This duality and blurring of the line between what were previously thought to be two completely distinct types of objects – asteroids and comets – is a key part of what makes these objects so interesting.”

The behavior of 248370 was discovered on July 7, 2021, in data from the Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) robotic astronomical study. Confirmatory observations taken by the Lowell Discovery Telescope showed clear signs of a tail, and a read of data from the Zwicky Transient Facility showed that the tail appeared as early as June 11.

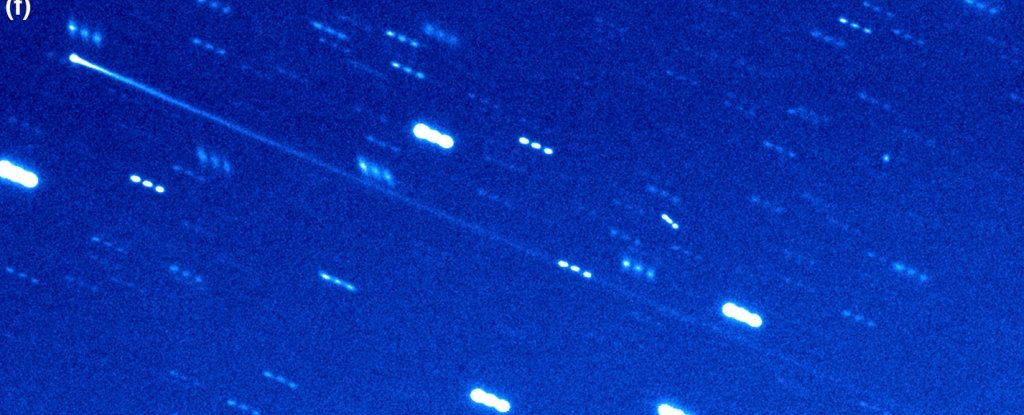

Between July 8 and August 14, new follow-up observations were made using different telescopes, confirming earlier data. There in the asteroid belt 248370 sported an absolutely stylish tail.

Measurements taken by Hsieh and his team revealed that the cometary nucleus – this is the piece of rock from which the tail extends – is about 3.2 kilometers (2 miles) in diameter. As of July, the tail was over 720,000 kilometers (450,000 miles) long, but only 1,400 kilometers (900 miles) wide. It’s crazy narrow compared to the length of the tail.

“This extremely narrow tail tells us that dust particles barely float out of the nucleus at extremely slow speeds, and that the flow of gas escaping from the comet that normally lifts dust from a comet into space is extremely low, ”Hsieh explained.

“Such slow speeds would normally make it difficult for dust to escape from the gravity of the core itself, so this suggests that something else might be helping the dust to escape.

“For example, the nucleus could spin fast enough to help throw dust into space that has been partially lifted by the escaping gas. Further observations will be needed to confirm the rotational speed of the nucleus, however. “

Other observations will also help us to better understand the object. Based on our understanding of the solar system, 248370 and the other main belt comets are not expected to exist. Indeed, it is believed that the main asteroid belt has existed since the formation of the solar system, around 4.6 billion years ago.

The asteroid belt lies between approximately 2.2 and 3.2 astronomical units from the Sun. The solar system’s frost line – the point beyond which it is cold enough for ice to form in a vacuum – is about 5 astronomical units. It is therefore not known why these main belt comets retained enough ice to produce cometary sublimation activity.

In addition, they could also help us understand the Earth a bit. In the early days of the solar system, impacts from water-carrying asteroids could have been one of the means by which water was transported to Earth. If the main belt comets have water, maybe we could explore this idea a little further.

“In the long term, 248370 will be well placed for surveillance as it approaches its next perihelion pass on September 3, UT 2026,” the researchers write in their paper.

“Monitoring during this time will be extremely valuable in further confirming the recurrent nature of the activity of 248370, limiting the orbital range over which the activity occurs (with implications for the depth of the ice on the object, as well as its active lifespan), measuring the initial dust production and comparing the object’s activity levels from one orbit to another and to other comets in the main belt.

The research was presented at the 53rd Annual Meeting of the AAS Division for Planetary Sciences, and was accepted into Letters from the astrophysical journal. It is currently available on the arXiv preprint site.

[ad_2]

Source link