[ad_1]

Editor's note: TThis article is based on the author's presentation at the ANU Malaysia Update 2018 conference, held in Canberra., Australia October 11-12, 2018.

COMMENT | Nearly six months after the Pakistani coalition Harapan won the 14th Malian legislative elections (GE14), urban voters swung between victory ecstasy, expectations of the impossible and measured assessments of results. Although there has been many stuttering and stumbling, the overview in the city centers remains one of stubborn faith in a better future for Malaysia.

But in the rural suburbs, where Malay voters traditionally supported the Umno-dominated BN alliance, the reactions to GE14's quite unexpected results were quite different from those of the urban reformists and the euphoric supporters of the new regime.

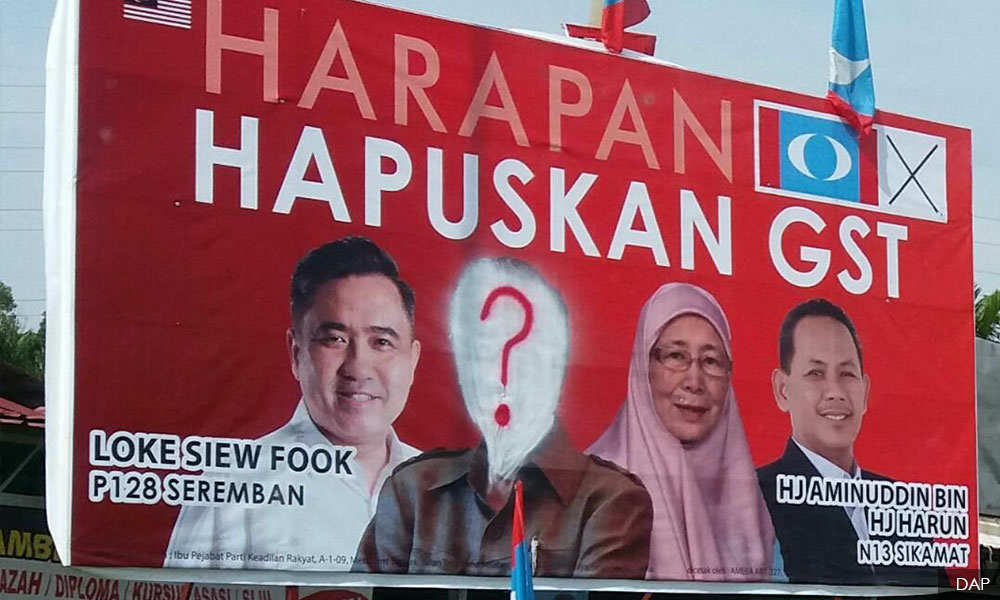

The pre-election rural voter analyzes (including mine) revealed concerns about the cost of living, the despair of the goods and services tax (GST), the loss of fuel and other subsidies as well as the disgust caused by the arrogant extravagance of the higher echelons of political society.

Unlike their urban counterparts, these voters were only concerned with their lived experiences: the difficulties they faced in putting food on the table, making ends meet and maximizing the ever decreasing value of their ringgit.

According to such analyzes, allegations of corruption in 1MDB were less irritating to rural voters than frustrations due to lack of access to favoritism, in the form of lucrative projects tightly controlled by low levels of authority such as village leaders and the leaders of associations.

Although politicians' demonstrations of unscrupulous wealth were highly controversial, such behavior was not unexpected, as many poor rural Malays accept their position at the bottom of the social hierarchy.

But when it came to predicting how the rural communities in which I lived would end up voting, I was wrong. The blatant injustice of their suffering in the face of the excesses of those who hold power and the expectations of further deterioration of their livelihoods have driven many people to vote against Umno leaders.

The shy voter of Pakatan?

My conversations with people in rural Johor post-GE14 showed that some had secret plans to vote for the opposition even as they tried to double their villages and BN blue neighbors.

Others took a last-minute decision as they headed for the ballot box and stood in front of the election ballot box. They then understood that they had suddenly confessed that they had voted against the generational practice of fully supporting Umno and BN.

Some who were uncertain were exasperated by the lack of respect shown for the former statesman, Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, even though they themselves were not his fans. Malay adat (cultural traditions) respect for elders and social etiquette have overcome political loyalties.

And yet, the results of GE14 still shocked voters as well as experts. Even though they voted for the opposition of the time, they never expected the fall of the entire government – especially in Johor, the proud place of birth of Umno.

The regret and despair were immediate. Even before dawn of the "next morning", I was aware of the following comments: "oh no, what did I do", and: "nothing n & # 39; It was really going with BN – it was just Najib. The new regime raised fears of even greater difficulties, considered unattractive to the rural poor. "Who will help us now?" Was a common refrain.

The disconnect between the rural poor and urban reformist centers is striking. After waking me up at the announcement of nightly celebrations in Kuala Lumpur, I returned to the fishing villages of West Johor, where there were men gathered in stunned silence.

Some strategies whispered to align with the new regime and the expected flow of premiums from new teachers; they knew no other way of working. Others have despaired that the new "Chinese government" eliminates Malay and Islam from Malaysia.

As the new government began to take steps to demonstrate more inclusive approaches to governance, the government's fears took a greater hold on rural people. In the east of Johor – where the Felda elders were supposed to be fake – the photos sent to WhatsApp of scraped bags filled with money and confiscated jewelry at the home of former Prime Minister Najib Abdul Razak Quickly followed by complaints that cast doubt on their authenticity.

False charts of a largely non-Malay government soon followed, all the more convincing as public appointments announced the appointment of non-Muslim Muslims to the positions of Attorney General, Chief Justice and Minister of State. Finance.

Umno's cybertroopers did not take the last place after the defeat, instead they intensified their racist rants. Members of the Umno branch, talking with friends and family in coffeeshops, repeatedly rehearsed anti-Malay, anti-Islamic or "attack" behavior, openly urging people to shed blood so that new government falls quickly. (I was present during these conversations.)

The indignation at so-called disrespectful actions of Islam is quickly spread through viral videos on social networks or WhatsApp. Umno Stalwarts firmly believed that the new regime would not last and that their return to power was only a matter of time.

Political intrigue and disruption of favoritism

When the dust cleared and the new government passed the 100 day mark, more measured and seemingly weighty comments circulated about the failure of the new government to keep its promises.

At that time, the GST was zero-rated and, although gasoline subsidies were not reinstated, the price of gasoline at 95 RON was fixed and not subject to global fluctuations. . Before the start of the Sales and Services Tax (SST), the outlook seemed slightly more positive.

Since then, a number of things have happened. Post-election analyzes showed that, contrary to the heady statements that took place immediately after the GE14 vote, Malay voters generally did not vote beyond their ethnic and religious votes.

Instead, as the vote of the non-Malay people almost completely shifted towards the new regime, the Malays spread their support between SAP and Umno, a number of them from the south accepting Amanah from PAS pro-Pakatan. Harapan and others in Kedah, for example for Bersatu explicitly Malay based on Mahathir.

At the same time, the issue of relations between Anwar Ibrahim and Mahathir has increased, as well as the possibility that Mahathir will revert to his gentleman's agreement on Anwar's installation as the next prime minister.

As public statements of loyalty and commitment were made, information about an internal conflict in PKR appeared, as well as rumors that Anwar was negotiating with Umno and that PAS and Umno were close to 'an official declaration of collusion.

But in the rural suburbs, people pay little attention to political positioning and political debate. Many do not understand political processes and do not really care about the wider implications of national policy discussions or political action. Most are only concerned about knowing if there will be an improvement in their lives.

At this stage, there was none.

While urban centers were punctuated by political debates and discussions about more progressive and transparent governance, Malaysian voters in the hinterland continued to question the new government's interest in their well-being.

People asked why it took so long to fire Najib and his wife Rosmah Mansor when there was so much evidence against them. They began to believe in the bravado of Najib and the new president of Umno, Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, and the conflicting accounts circulated on social media that there may not have been any concrete evidence of related crimes. at the BMD.

The government's new crackdown on Umno funds has added to their daily lives. Those who depended on it for their survival, having no money to spend on political gains, suffered even more. This was deepened when the OSH came into effect.

Former village chiefs have quietly decided to isolate the appointed members of the new regime, giving the impression that everything could be done only through the intermediary of their network and making new leaders responsible not important. When former representatives were unable to fulfill what they had promised (because they had lost authority), the blame was clearly blamed on the "incompetence" of the new government.

In Johor, the new state government of Pakatan Harapan has faced similar challenges. Even when public announcements regarding changes in the state administration – with new benefits offered to the poor – were met with disbelief.

The promises made by the campaign to the Felda settlers are not yet fulfilled, and the poor Malay living outside the Felda settlements have few means or understand how to access the new offers of the government.

Instead, they hear about job losses among government officials, increases in the price of cigarettes, the crackdown on the sale of contraband cigarettes (cheaper, untaxed versions of many rural people are still dependent), and an imminent ban on smoking in green spaces; while adding to the perception that they are unjustly targeted.

Even more recently, the marine police arrested fishermen who were transporting passengers to tourist sites to provide them with additional income, while others, fishing without official permits, were also arrested and questioned.

For these rural populations, the need for order, the "rule of law", regulation and security mean less than their ability to make money to survive. The financial aid granted by the old political channels having been abolished, the removal of these means until then undisturbed to increase the incomes of the households is added to their difficulties and to their negative vision of the new regime. .

Listening to the hinterland

Where can this discontent go? I saw that instead of joining a new Malaysia open to all (despite the constitutional laws on the particular position of the Malays and Islam), the rural Malaysian poor were regressing deeper and deeper into ethno-religious lodges.

In order to strengthen the support of rural Malays and to counter Mahathir's comments about the "lazy Malay", Anwar himself would have liked to put more emphasis on the rights of Malays. He has resumed calls for Malay exclusivity and has publicly manifested his allegiance to the royal institutions.

While the SAP maintains its conservative Islamic stance without compromise, members of the new government turn around on religious issues, addressing the gallery and opting for "safe" religious proclamations to preserve and develop a wider support between Muslims and Malays.

When fears are exacerbated and perceived injustices are highlighted, it is easy for ethno-religious abysses to spoil extreme thought. In rural areas where alternative or more moderate religious voices are disdained as "liberal", efforts for inclusiveness are tainted by statements of disloyalty to beliefs and deviance from the Islamic faith.

It was interesting to note that my conversations with rural Johorian women revealed a perceived need on their part to show greater piety to their men and a visible adherence to the letter of faith.

Several women opted for PAS as a more religious option than Umno at the polls; PH was considered too secular. Despite their previous comments to GE14, PAS representatives in their neighborhoods were hypocrites.

Where, in the past, Wanita Umno clung to women in rural areas and was mingled with social acceptance and peer pressure to vote like the BN, GE14 seems to have been lost to internal struggles in the ranks of women and disenchantment with the selective payment of funds. assistance. There was also the paramount need to vote for a candidate who would behave well against religious norms and thus gain the voter's merit for the after-life.

The chart I draw here may seem to be the extreme opposite of the hope that bubbles remain in urban centers after GE14. But the reality on rural Malay land is hard.

These constituents simply want to see that they get some help, that their lives improve and that they too can access the benefits marketed by the new government.

As these seemingly remain out of their reach, the magnitude of the schisms that can arise from fear and despair varies. At its lowest level, it may continue to be simply the need to "take care of our own species" (Jaga Orang Melayu Kita), or it could switch to far more extreme extremes of hate and radical action.

The new government of Pakatan Harapan must be seen as truly involved with marginalized people to prove that they have not been forgotten.

While the recently released budget details many benefits for the "40% of the poorest" (B40), with no concrete improvements in their livelihoods or visible change in conditions on the ground, these plans are pure rhetoric. Because in these remote rural areas of Peninsular Malaysia, there is little Harapan (hope) left.

This article was published for the first time in New Mandala.

SERINA ABDUL RAHMAN is Malaysia's Visiting Scholar at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, conducting research in the areas of sustainable development, environmental anthropology and the economy. of the environment. Serina co-founded Kelab Alami, an organization created to empower a fishing community in Johor through environmental education for habitat conservation and economic participation in coastal development. She obtained her PhD in Science from Teknologi Mara University in 2014.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author / contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

[ad_2]

Source link