[ad_1]

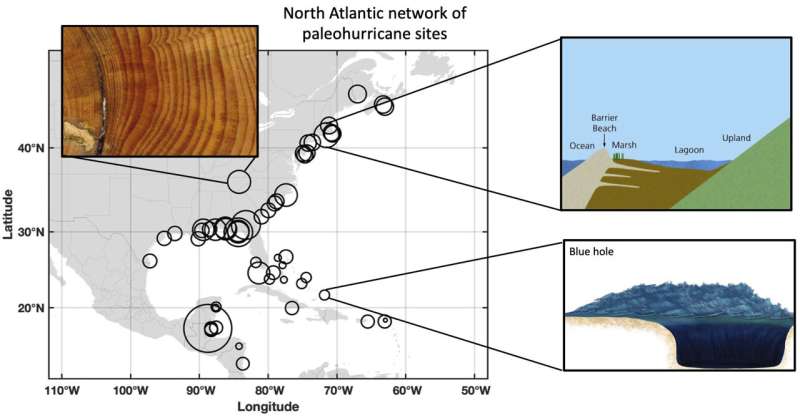

The North Atlantic site network that preserves hurricane records stretches along the coast from Canada to Central America, but with significant gaps. A new study by scientists at Rice University shows that filling these gaps with data from the mid-Atlantic states will help improve storm history over the past thousands of years and could help predict future storms in times of climate change. Credit: Elizabeth Wallace / Rice University

Atlantic hurricanes don’t just come and go. They leave clues of their passage through the landscape that last for centuries or more. Rice University scientists are using this natural record to find signs of storms hundreds of years before satellites allow us to observe them in real time.

Postdoctoral fellow Elizabeth Wallace, a paleotempestologist who joined climatologist Rice Sylvia Dee’s lab this year, draws on techniques that reveal the frequency of hurricanes in the Atlantic Basin over millennia.

Paleoclimatic hurricane data (or ‘proxy’ data) is found in records such as tree rings that retain signs of short-term flooding, sediment in blue holes (sea caves) and coastal ponds that preserve evidence of sand washed inland by storm surges. These natural records give researchers a rough idea of when and where hurricanes made landfall.

In a new paper in Geophysical research letters, Wallace, Dee and co-author Kerry Emanuel, a climatologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, take hundreds of thousands of “synthetic” storms from simulations of global climate models of the past 1,000 years and examine whether they are captured or not. through the vast network of Atlantic paleo-hurricane proxies.

Rebuilding the past will help scientists understand the ebb and flow of Atlantic hurricanes over time. Previous studies by Wallace and others have shown that a single site capturing past storms cannot be used to reconstruct climate change from hurricanes; however, a network of proxies could help refine models of how these storms are likely to be affected by climate change in the future.

“These paleo hurricane proxies allow us to reconstruct storms in the past, and we are using them to understand how basin-wide storm activity has changed,” said Wallace, a Virginia native who graduated from PhD at MIT and Woods Hole Oceanographic. Institution last year and connected with Dee when the professor spoke there in 2017.

“If I have a Florida sediment core, it only captures the storms that hit Florida,” she said. “I wanted to see if we could use the comprehensive collection of recordings collected from the Bahamas, the East Coast and the Gulf of Mexico over the past decades to accurately reconstruct basin-wide storm activity over the course of the years. of the last centuries. “

The man-made storms they built helped illustrate what Wallace already knew: there is a bias toward the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, and a need for more proxies along the eastern coasts of North America. and central. The Rice team’s quest going forward will be to refine their climate simulations and add more sites to the networks to better reconstruct past hurricane activity.

“In particular, there aren’t really any sites in the Southeastern United States, places like the Carolinas,” she said. “One of the goals of this work is to highlight where scientists should go next.”

Wallace has first-hand experience in core drilling. “In a storm you get strong winds and waves that pull the sand off the beach and essentially throw it back into a coastal pond,” she said. “It is only during storms that these layers of sand settle in the pond, and in the sediment cores you can see them interspersed with the fine mud that is usually found there. We can date these layers from sand and find out when a hurricane hit the site. “

She noted that there had not yet been an “intensive” effort to compare the records of sediment and tree rings. “Tree registration is always an uncertain proxy,” Wallace said. “We are looking for tree ring records with rainfall signatures that match storms from the past 200 or 300 years that match sediment records for that same interval.”

Dee said the work is fundamentally different from the paleoclimatic models she studies most often. “Here we take climate models and generate hundreds of pseudo-tropical storms,” she said. “We ‘play Gaia’ by creating a plausible version of reality and combining it with our knowledge of available proxy sites.

“This tells us how many records of how many locations we realistically need to capture a climate signal,” Dee said. “It’s really expensive to go out and drill core, and it helps us prioritize where to drill.

“This research is crucial as we accelerate towards an average climate state with increasingly warmer temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean,” she said. “Understanding how these storms have evolved over time provides a baseline for assessing tropical cyclones with and without human impacts on the climate system. “

A Pan Postdoctoral Fellowship and a Rice Academy Fellowship to Wallace and a Gulf Research Program Grant to Dee supported the study. Dee is an Assistant Professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences. Emanuel is Cecil & Ida Green Professor of Atmospheric Sciences and Co-Director of the Lorenz Center at MIT.

Unraveling the drivers of past hurricane activity

EJ Wallace et al, Resolving long-term variations in North Atlantic tropical cyclone activity using a pseudo-proxy paleotempestology network approach, Geophysical research letters (2021). DOI: 10.1029 / 2021GL094891

Provided by Rice University

Quote: Natural Archives Reveals Atlantic Storms Across Time (2021, September 7) retrieved September 8, 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2021-09-natural-archive-reveals-atlantic-tempests.html

This document is subject to copyright. Other than fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.

[ad_2]

Source link