[ad_1]

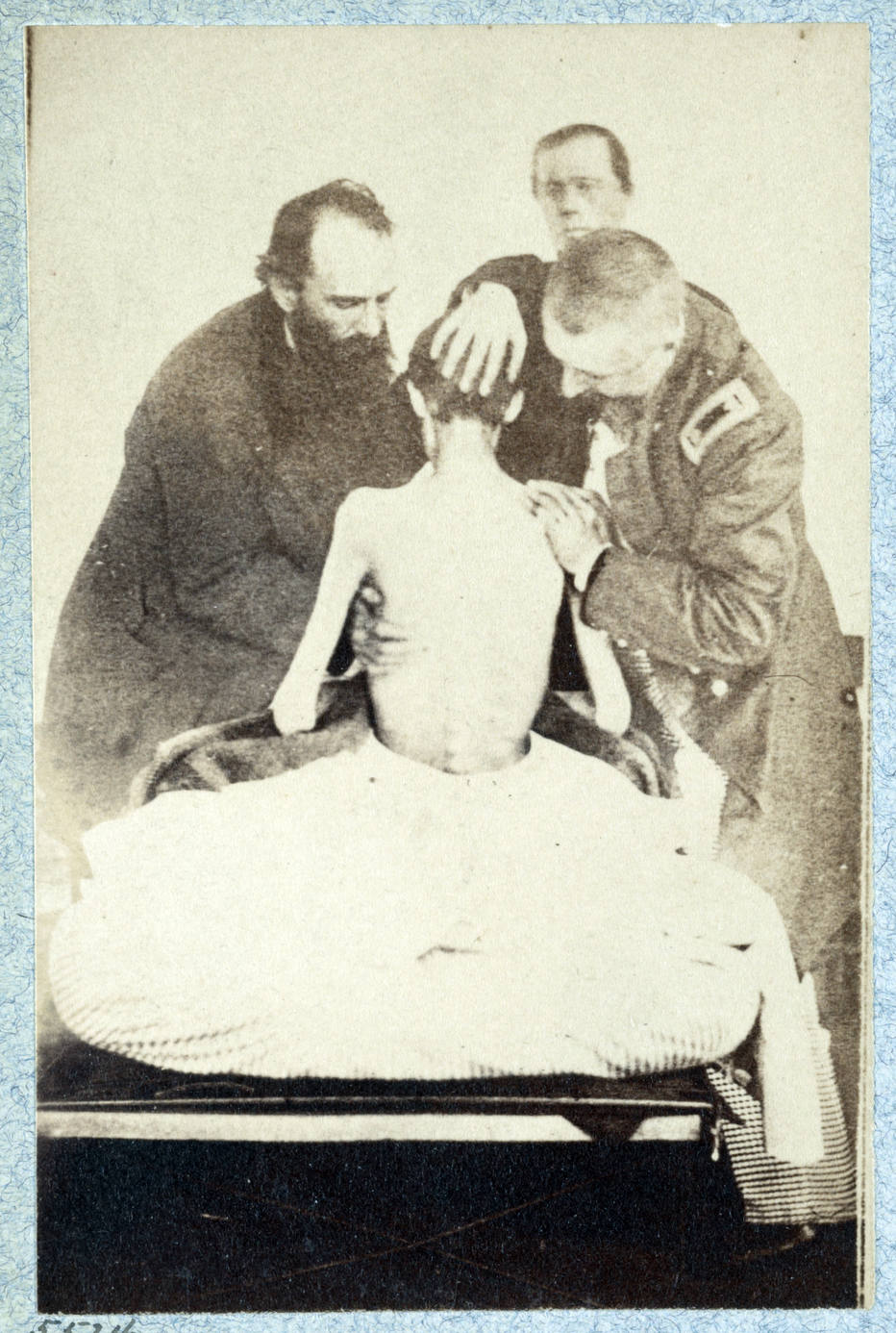

In mid-October, Californian researchers published a study on prisoners in the American Civil War that led to a remarkable conclusion. Male prisoners of war who were mistreated were about 10% more likely to die than their peers from the middle age, the study reported.

The result, the authors conclude, suggests an "epigenetic explanation". The idea is that the trauma can leave a chemical mark on a person's genes, which is pbaded on to subsequent generations. The mark does not damage the gene; there is no mutation. But it changes the mechanism by which the gene manifests or is transformed into functional proteins.

The field of epigenetics gained ground about a decade ago when scientists reported that children exposed, still in the uterus, to the Dutch winter of hunger, a period of extreme privation at the end of the Second World War, their genes a specific chemical brand, an epigenetic signature. The researchers then linked this outcome to differences in children's health throughout life, including above-average body mbad.

The excitement has intensified, generating more studies – on the descendants of Holocaust survivors, for example – that indicate the heredity of the trauma. These studies suggest that we inherit certain traits from the experience of our parents and grandparents, particularly their suffering, which in turn changes our own health – and perhaps that of our children.

But the work provoked a dispute between researchers. Critics argue that the biology involved in such studies is simply not plausible. But researchers who promote the notion of epigenetics argue that their evidence is strong, even though they have not yet found answers in biology.

"These are extraordinary statements, but they advance on the basis of very ordinary evidence," said Kevin Mitchell, badociate professor of genetics and neurology at Trinity College Dublin. It's an evil of modern science: the more extraordinary, sensational and seemingly revolutionary the statement is, the lower the level of evidence on which it is based, whereas it should be the opposite. "

Experts say the criticism is premature.Studies on rats have been cited as evidence of the transmission of trauma." The effects we found were small, but remarkably consistent and significant, " said Moshe Szyf, professor of pharmacology at McGill University in Montreal. "That's how science works. At first, everything is imperfect, but the more you search, the stronger it becomes. "

The debate revolves around genetics and biology.The direct effects are one thing: when a pregnant woman drinks too much, it can cause fetal alcohol syndrome, because stress in the body of a pregnant mother is shared with the fetus, which directly interferes with the development program of the uterus.

But no one can explain exactly how changes in brain cells caused by abuse could be communicated to a sperm or to a fully formed egg before conception.And this is only the first challenge.After conception, when the sperm meets the egg, there occurs a natural process of cleansing , or "reboot," which eliminates most of the chemical make-up of genes Finally, as the fertilized egg grows and develops, a symphony of genetic remodeling begins as cells begin to specialize in brain cells, epithelial cells, etc. How could a signature of trauma survive all this?

One of the theories is based on animal research. In recent studies, scientists at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, led by Tracy Bale, have created male mice in harsh environments, periodically swinging their cages or leaving the lights on at night. This alters the subsequent behavior of such mouse genes so as to alter their way of managing stress hormone epidemics.

And this change is badociated with changes in the way your children handle stress: in general, these young mice are less reactive to hormones than animals that have not been tested, Bale said. "These are clear and coherent results," she said. "The field has progressed a lot in the last five years"

[ad_2]

Source link